What do a psychedelic album cover, the robot from Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis,” the Declaration of Independence, Renaissance architecture, and the Garden of Eden have in common?

All are, in one way or another, expressions of the utopian impulse, according to a wide-ranging exhibit at the New York Public Library, “Utopia: The Search for an Ideal Society in the Western World.” It brings together hundreds of books, posters, pamphlets, prints, photographs, film clips, letters, bits of music, medieval manuscripts, Soviet propaganda, anti-war buttons, and other historical materials in what is one of the largest exhibits the library has ever presented.

Organized in cooperation with the Bibliotheque nationale de France and filling galleries on two floors of the Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street building, this is an exhibit that casts its net wide and strives to bring as much visual life as possible to what is, in effect, a purely philosophical or literary concept.

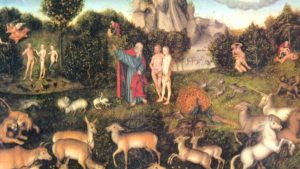

The Garden of Eden, as rendered here by Lucas Cranach the Elder, was a utopian template.

Judging by the number of spin-off events – lectures, film series, Web sites, performances, and courses at colleges and museums all over the city – our time seems ripe for a utopian revival, although, according to this show, all times are. Utopian thought, we learn, is a deep undercurrent that has run through every century. In fact, by the time you leave this exhibit, you may find yourself believing that utopian drives – not love, sex, or money – is what has made the world go ’round.

The exhibit looks not just at those consciously designed blueprints for better societies such as Plato’s “Republic” or Sir Thomas More’s “Utopia,” but at age-old myths or beliefs in worldly – or otherworldly – paradises. These include the Garden of Eden, the Golden Age of the Greeks, New Jerusalem, El Dorado, and Atlantis.

It also chronicles those actual experiments in utopian living, most of which were carried out in North America in the 18th and 19th centuries, such as Oneida in New York and New Harmony in Indiana. The exhibit’s final section looks at how utopian ideas have also transformed mainstream societies – and often the course of history. The most dramatic examples are the French and American revolutions and the spread of communism in the 20th century.

Utopia has meant different things to different people. The Shakers tried to create a society without sex, even for procreation (religious conversion was supposed to provide a steady flow of new members), while the Oneida community practiced “complex marriage” in which husbands and wives were shared. Ancient Sparta was considered utopian by some, despite its reliance on slavery, because individuals subordinated their needs to that of the city-state, while even the Nazis had their own perverse utopian goals in their ideas of improving humanity through eugenics, creating, by their logic, a master race.

Utopianism, we learn, also has its ironic and satiric side. The word itself, coined by More as the name for his fictitious island, is a pun meaning both “good place” and “no place.” Satires on utopias are almost as old as the serious tracts, and Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” is probably the best known.

More, who wrote his book in response to social ills and inequalities in Renaissance England, was the first to describe a place that was, in theory, achievable by ordinary humans. In his pre-Marx, communist society, everyone’s house was identical, and money was unnecessary because everyone drew freely from communal warehouses to which all contributed.

The discovery of the New World provided a blank slate for Europeans to project their utopian fantasies. Colorful prints show the indigenous populations as, alternately, noble savages or vicious cannibals. In their ideas for perfect communities on this new soil, many of the Renaissance utopians turned to classical ideas of proportion and urban planning, although the rigid controls that utopias are sometimes known for comes across in strict grid plans, such as that for Savannah, Ga.

After More, the fictitious travelogue became the favored literary genre for utopian fantasies. These included Francis Bacon’s “New Atlantis,” where humanity’s problems are solved by science and invention, and such romantic novels about Shangri-Las as Samuel Butler’s “Erewhon” and Edward Bellamy’s “Looking Backward.” With the advent of science fiction, utopias began cropping up on other planets.

Utopia’s evil twin is dystopia, the result of some slip between conception and execution, a situation best illustrated – unfortunately for us – by 20th century examples. Titled “Dreams and Nightmares,” this section has at its entrance a replica of the robot from “Metropolis,” the early silent movie about technology run amok. A copy of Karel Capek’s 1923 play in which he coined the word robot, from the Czech word robota, reminds visitors that its root meaning is drudgery.

Utopian literature goes distinctly dystopian with George Orwell’s fantasy of a totalitarian state, “1984”; Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World”; and Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451.”

Soviet propaganda posters from the early years after the revolution show heroic men and women wielding scythes and raising sheaves of wheat over their heads, while nearby are bleak photographs from the Stalinist gulags of the 1930s.

The exhibit pulls together a colorful array of utopian threads from the counterculture flowerings of mid-20th century America: communes, Haight-Ashbury hippies, Woodstock, civil rights, feminism, and gay rights.

These broader cultural manifestations of utopian idealism provide some of the most diverting images in the show, although they fall outside a strict definition of utopia.

Easily overlooked are the less free-associational displays, such as that on contemporary “intentional communities” in America. Too little is said about these serious experiments with actual utopian living. Some have been going on for quite a while, such as the Virginia community founded in 1967 on the principles put forth in B.F. Skinner’s “Walden II.” One wonders, do the children there wear lollipops around their necks to develop frustration tolerance, as the behavioral psychologist described in his utopian fiction? Or, did that prove too dystopian? Alas, there is only one photo of a few buildings, and not a person in sight.

Nor is enough said about the Israeli kibbutzim, probably the century’s most important experiment in utopian communal living, which are said to have lost much of their early idealism.

It’s said that the standard of living in the world has never been higher. The most affluent billion people live in galloping pursuit of a happiness never dreamed of by Thomas Jefferson and other idealists. Yet, technology, consumerism, and ecological problems have given rise to fantasies more along the lines of “Brave New World” than Shangri-La. But, as this exhibit makes clear, utopias and dystopias are different sides of the same coin, less real blueprints than reflections of the hopes and fears of the real world we live in.

New York Public Library

2000