“American Anthem” is the second show at the new American Folk Art Museum. If the first was overshadowed by the opening of the new building itself, then the second should be the one where the building —which was showered with accolades, including some from me—would get down to the more self-effacing job of displaying the art.

But when I went to look at the art, it didn’t feel that way. The building kept intruding and distracting me.

There are some serious architectural problems here that were overlooked, I think, in the post-Sept. 11 outpouring of goodwill that attended the museum’s opening. The $22 million building—the first permanent home for the once nomadic museum—became a symbol of faith and optimism about the city’s future.

The facade of the American Folk Art Museum.

And it was hard not to be dazzled by the architectural pizazz of Tod Williams and Billy Tsien, New York architects who were doing their first big New York project. Their key decision was to carve a five-story atrium in the center of a very narrow building and to use various slots, peepholes, and stairways to add to the sense of airy connection between the floors. They succeeded all too well, with the result that the areas for displaying art are often too narrow and feel more like landings than galleries.

Fortunately, folk art is resilient – or it wouldn’t have made it this far. The experience is like visiting dear old friends who have chosen to live in an overdesigned house that seems at odds with their personalities. “American Anthem” draws on the museum’s great permanent collection and reshuffles the deck a bit, repositioning the pieces in new arrangements based on social or aesthetic currents. You’ll see whirligigs and weathervanes, stenciled bellows and painted duck decoys, Frakturs, dolls, and a carousel horse. There’s every kind of quilt, from crazy quilts and album quilts to a flag quilt, string quilt, bars quilt, and a tree of life quilt. There are paintings infused with religious fervor, paintings infused with socialist fervor, and paintings infused with every other possible fervor including bizarre and claustrophobic works by outsider artists such as the reclusive Henry Darger and the institutionalized Martin Ramirez.

“Flag Gate” from 1876

The show kicks off with the iconic “Flag Gate,” from 1876, the centennial year of America’s independence. A functioning gate, it has carved, wavy wooden stripes that look like they’re rippling in the breeze.

Don’t miss “Noah’s Ark,” a piece that doesn’t really fit here, in that it was made neither in America, nor by an American, but by an anonymous prisoner of war in England (it is meant to juxtapose with the liberty-inspired works). Carved mostly from animal bones recycled from prison kitchens, it looks to have been done during a long internment, judging by the meticulous detail and the elaborate architectural construction, including movable parts that showed the animals boarding the ship.

Not all folk art was intended as art. Reflecting a mid-19th century atmosphere of reform and social theories – that sometimes shaded over into pseudoscience — is the “Phrenological Head,” which uses a colored, map-like diagram on a mannequin to reflect the 37 purported “faculties” responsible for human behavior.

Stories are often told of folk artists laboring in their spare time at ambitious projects that take years to complete. So it is with a secretary cabinet made between 1862 and 1869 by a railroad woodworker named Frederick Stedman Hazen. The elegant piece is far from folkish. It uses 21,378 pieces of inlaid wood, including some with famous associations, such as those from the steeple of Independence Hall, Mount Vernon, the ships Endeavor and Constitution, and some associated with Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. Hazen, who gained fame during his lifetime for the project, mounted and labeled a sample of each piece of wood he used, noting its location on the secretary.

The show has an interesting group of late-blooming naïve painters, such as Victor Joseph Gatto, a boxer, laborer, and convicted robber, who took up painting after seeing the prices at a Greenwich Village sidewalk show. Vowing he could do better, Gatto became successful with works such as the Henri Rousseau-inspired jungle scene shown here, painted in 1942.

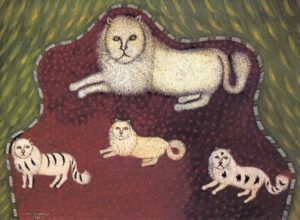

Morris Hirshfield didn’t begin painting until he was in his 60s. The former garment industry entrepreneur is best known for his animal paintings, such as “Mother Cat With Kittens,” with his characteristic Egyptian-style flatness and the domestic cats endowed with furry manes like male lions.

Morris Hirshfield’s “Mother Cat With Kittens.”

Outsider artists, whose visionary approach to art sets them apart from the naïve artists, include the Southern Baptist lay preacher Howard Finster, who died this year at age 87. In 1976, he had a vision that told him to create sacred art. His paintings are didactic and diagramatic, mixing images of the modern and the biblical, such as an airplane with clinging angels.

Here, then, is the full richness of the American folk tradition. The art is terrific, the installation is well done, but … that building. Wouldn’t something a bit more plain and folksy have been better, instead of these 50-foot vertiginous drops, the redundant stairways, the offbeat blends of sandblasted concrete, metals, green fiberglass, and precious woods? But, high-profile buildings are what museum boards want nowadays. And in a way, the building makes a statement about the changing face of folk-art collecting. The art may have humble origins, but it is no longer displayed in humble spaces.

The American Folk Art Museum, NYC

2002