Jesse Helms take note. Sex is no longer a preoccupation of the avant garde. Today’s fringe culture has graduated from images of sadomasochism and the like to … death. Death and decay. The pleasures of the flesh are out. The terrors of the flesh are in.

Andres Serrano, once notorious for submerging a crucifix in urine, has moved on to lavish photographs of murder victims on morgue slabs. Photographer Joel-Peter Witkin creates morbid tableaux populated by the grotesque and the diseased. Others specialize in bottled specimens – fetuses, animal parts – in a genre that’s become so popular it’s known as formaldehyde photography.

Perhaps it has something to do with the AIDS epidemic. Or, the aging of the baby boomers. Or the approaching end of the millennium. Or contemporary art’s need for something new that shocks.

The latest manifestation of this trend is a Soho exhibit titled “Beyond Ars Medica.” The objects in it are not the work of any contemporary artist, but are samples from Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum, a 19th century collection of anatomical anomalies, diseased organs, medical instruments, skeletons, and the like. Although intended by its major benefactor, surgeon Thomas Mutter, as a teaching collection (it is still operated by the American College of Physicians, based in Philadelphia), it has always attracted curiosity-seekers. And, so many contemporary photographers have found its collection so matched to their new taste for the bizarre that their works have been put into a calendar, now in its third year of publication.

It is an exhibit that would warm the heart of P.T. Barnum. Step right up, ladies and gentlemen and see the amazing horned woman. Yes. This 19th century French citizen, nicknamed Widow Sunday, sprouted a 10-inch protuberance from her forehead. A model of her face, showing the drooping horn, can be seen in a photograph at the Soho gallery.

Or how about the famous Siamese twins, Chang and Eng? Members of the college had performed the autopsy on the pair, and the museum was allowed to retain their connected livers along with a plaster cast of their torsos, also shown here in a photograph.

With the exception of a petrified ovarian cyst the size of a beach ball, and which weighed 70 pounds when removed, most of the borrowed specimens on view in Manhattan are wax models. Some show faces ravaged by disease, such as the man whose lips and cheeks were destroyed by gangrene, other faces are deformed by pustules or tumors, or flayed to show the insides for the purpose of medical education.

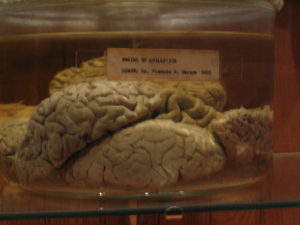

Every once in a while, something has that startling presence of art, like the photograph of a cross-section of a human head, cut into a thin profile slice, which allows you to see the shapes and positions of everything inside, the brain like a halved cauliflower, the lumpish masses of the tongue and eyes, the spaces of the sinus cavities, the densely packed arteries, veins, muscles, and nerves. Other works trigger a more emotional response, horror at nature’s random cruelties, the incredible burdens that some people must carry, and, of course, the inevitability of suffering and death.

Included in the displays of medical equipment, is a Victorian tonsil “guillotine,” the medical kit of a physician who accompanied an arctic exploration team and was frequently called upon to amputate frostbitten, gangrenous feet and toes. Also displayed is a collection of objects removed from children’s food and breathing passages: jacks, tiny metal animals, and toy ships.

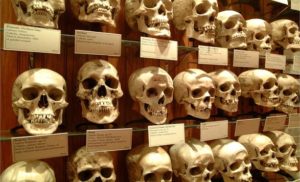

Some of the Mutter’s most famous holdings can only be glimpsed in photographs. Like the conjoined skeletons of twins whose two skulls melded into one, giving the appearance of a human with four legs and four arms. Or the photograph of a group of fetal skeletons, all mounted in an upright position so that the group looks like an X-ray photograph of children clustered in a playground.

Those photographs of the Mutter Museum’s interior show a Victorian setting of glass-fronted oak cabinets, green-shaded lamps, and spotlighted specimens, reminiscent of a setting in a Jules Verne story. And there’s something comforting about that antiquated atmosphere, because it puts a distance between us and the victims of all these diseases and mishaps, and allows us to gawk without feeling guilty.

Here and there, throughout the show, however, the mood shifts from Jules Verne to P.T. Barnum, from the gentleman’s curio case to the old circus freak show. Perhaps it’s the photographs of the shrunken heads created by the Jivaro Indians of Ecuador, or the cast of a foot of a 14-year-old Chinese girl deformed by foot-binding that is displayed in a satin-lined case. Or the photograph of the man with the Brooklyn Bridge tattooed across his back.

One of the hypocrisies of our time is that we gawk just as much as the Romans or the Victorians – they had nothing to match our daytime talk shows – but we don’t admit what we’re doing. We have to dress it up with psychobabble, or the pretense of “giving the news,” or, as in this case, the facade of art.