It’s no wonder that Frida Kahlo is a cult figure. She has more dimensions than string theory. Do you like stories of people overcoming terrible handicaps? Frida was partially crippled by polio as a child, then suffered unimaginable injuries in a bus accident at age 18. She had lifelong pain and heartbreaking miscarriages that haunted her art.

You like stories of tempestuous romance? Frida married the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, a compulsive womanizer who had a lengthy affair with her younger sister. Diego and Frida were divorced, but remarried and stayed so until her she died at 47.

You like glamour and fashion? Diego and Frida romped through international high society, charming everyone with their verve and style. Frida designed her own clothes, doing variations on traditional Mexican dresses with snug embroidered bodices and long flowing skirts in brilliant colors.

She was a strong-willed feminist who refused to pluck the infamous unibrow that, rendered in numerous self-portraits, became part of her iconic image.

Kahlo was fearless as an artist, a surrealist whose imagery was bizarre even by surrealist standards. Using dreamlike symbolism, she exposed all her most personal obsessions and passions. She depicted her indelible attachment to Rivera in “Diego on My Mind,” in which Rivera’s face stares out of her forehead like a third eye.

All this has been treated in books, exhibitions and film. Was there anything new that an art institution could do with Frida Kahlo? Well, the New York Botanical Garden, of all places, has taken a shot at it with an exhibition about Kahlo’s association with plants: “Frida Kahlo: Art . Garden . Life.

It’s not as farfetched as it might sound. Kahlo was fascinated with all aspects of the natural world. She kept monkeys and other exotic pets. She grew native Mexican flowers and plants in the garden of La Casa Azul, the blue-walled house where she lived in Coyoacan, on the outskirts of Mexico City. And certainly she used botanical imagery in her paintings, both naturalistic and surrealistic.

Actualy, it’s not a bad fit for the New York Botanical Garden, an otherwise down-to-earth institution with a penchant for the bizarre when it comes to art. It is forever doing odd things with plants, from shows devoted to renderings of weird flora by botanical illustrators to the holiday train show with its detailed villages made entirely out of bark, leaves and other crunchy materials and, just last spring, a mannerist-inspired display of grotesque and gigantic face sculptures made from fruits and vegetables.

Compared to some of that, Kahlo doesn’t look all that far out.

The evocation of Kahlo’s gardens in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, a grand Victorian greenhouse, is pretty tame. There, you learn that Kahlo liked sunflowers, zinnias and fuschia and see a replica of a centerpiece of Kahlo’s garden, a stepped pyramid on which are arrayed terra-cotta pots filled with Mexican cacti and succulents.

But it lays the groundwork for the display of 14 paintings in the Botanical Garden’s library gallery.

Who knew that Frida Kahlo paid tribute to Luther Burbank, the pioneering American botanist about whom everyone learns in grammar school? But, of course, she gives the portrait a surrealist tweak, so that Burbank is planted in the ground like a tree, his roots feeding on a buried corpse, a reflection, the wall text helpfully tells you, of Kahlo’s interest in cycles of life and death.

She put a twist on traditional still life compositions – tables covered with such tropical fruits as mangos, guavas, oranges, and bananas– by teasing out sexual shapes from cut-open melons and other seed-laden structures. In one still life, she planted a small flag in a melon that pays tribute to her dentist, Samuel Fastlicht, one of many medical professionals she befriended in the course of a lifetime of medical treatments.

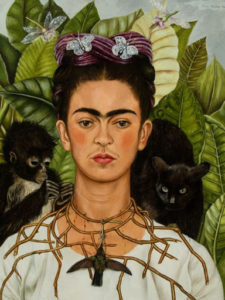

The masterpiece of the show is one of those Kahlo self-portraits in which she surrounds her realistically rendered face with all manner of symbols. She wears a necklace of thorns that sends droplets of blood down her neck. White moths perch on her hair like hairclips, a black monkey hangs on one shoulder and a black cat on the other, while a dead hummingbird dangles from the thorn necklace. According to Mexican folklore a dead hummingbird was supposed to entice the wearer’s lost love to return.

The show is a bit thin, not really up to museum standards. But because it’s the New York Botanical Garden, and this is spring, and Kahlo is such a colorful character, it all seems like good fun. Especially when you contemplate all the jolly events and programs the Garden has coaxed out of its subject: “Frida al Fresco” evenings, lectures on Diego and Frida, family scavenger hunts, puppet shows, Mexican films, and “Cooking with Frida.” And don’t forget the gift shop with its Frida Kahlo postcards, scarves, handbags and oven mitts.