Winter is the least painted of all the seasons. Bruegel and some of his northern contemporaries painted lovely winter landscapes, because they painted everything in the studio and never took canvases outside. The impressionists, committed as they were to plein air painting, mostly ignored the tempting visual effects of snow and clear air. Even the hardy Vincent Van Gogh, who strapped his canvas to its easel during a wind storm and put candles on his hat to paint night scenes, tended to work indoors during winter.

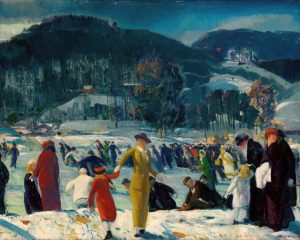

But, around the turn of the century in America, a group of urban realists – some of whom were part of the so-called Ashcan School – began painting gritty city scenes – El trains, construction projects, burlesque houses, amusement parks, and hobos. And part of this attitude of taking on whatever was out there included an affinity for cold, wintry scenes.

Among them, and one of the best, was George Bellows (1882-1925), whose snow scenes are numerous enough to constitute an entire show. Such an exhibit, organized by the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Fla., of all places, is now at the Newark Museum.

“George Bellows: Love of Winter” presents 23 winter scenes painted between 1908 and 1915. Many of the paintings are views across the Hudson River from Riverside Park to the Palisades – a scene that will have a familiarity to the local audience. Others are powerful images of the city, such as the 1909 work “Pennsylvania Station – Excavation,” which shows, in a spooky nighttime scene, the giant pit above which the famous McKim, Mead and White building was constructed.

Another group of pictures focus on the landscape around Zion, near Princeton, where Bellows spent a working holiday with his roommates, painter Ed Keefe and future playwright Eugene O’Neill. The trio arrived just after a major snowstorm, and stayed at the O’Neill family’s summer home from Jan. 19 through Feb. 12, 1909.

What did Bellows see in snow? He found amazing color in it for one thing. If Eskimos have 17 words for snow, then Bellows, the artist, has at least that many ways of rendering it. He loved the blue, gray, and greenish shadows that snow gathers, as in “Winter Afternoon,” a view across the blackishly cold Hudson, a scene that has the intense brightness of a sunlit day after a big storm.

He could render the ice floes on the river with the sparkling iridescence of an impressionist in little blue, blue-green, and blue-black strokes. But Bellows wasn’t an impressionist; they tended to use nature as a static motif. He was too taken with the forces of nature, too in love with drama for that. His paintings are more dynamic, with winds parting the clouds and kicking up whitecaps, of bending trees and struggling tugboats sending out great puffs of smoke.

He wanted to capture the precise kind of weather, or the time of day, and to animate his scene with human activity. In “Blue Snow, The Battery,” it’s early morning after a snowfall, when the white stuff is undisturbed save for narrow paths and you can almost feel the cold dampness coming off the white, blue-shadowed expanses.

Bellows is sometimes hard to classify. He often wields the brush with an expressionist fervor – big broad swaths of water or earth, scruffy branches scraped right into the pigment, white clouds laid on with a pallet knife, little flicks of the brush for whitecaps or distant houses.

Other times, he is a tonalist, composing his paintings around one color as in “Up the Hudson,” a predominantly yellowish-green picture of late winter’s subdued colors. “North River” is a bluish-black picture of winter at its darkest and coldest. Other times, he constructs his picture around a strong dark and light composition, as in “Noon,” with the bold black horizontal of the elevated railroad tracks dividing the picture.

There isn’t a boring picture in this show. Bellows was a vigorous and passionate artist who seemed to pour himself into every picture as if it were his last.

Augmenting the show is a companion exhibit, “Blanketed in Snow: American Winter Scenes,” of similar motifs by contemporaries of Bellows, such as Childe Hassam, William Glackens, Robert Henri, Ernest Lawson, and photographs by Edward Stieglitz. Don’t miss Robert Henri’s late-evening river scene in which the snow falls like confetti and the sky and water are the exact color of pea soup.