Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) was the archtypical modern artist, which is to say that he was riddled with doubts. That sounds like a liability for a creative person, but in the hands of a great artist — think Kafka, Beckett, Auden —doubts become profound and exquisitely subtle uncertainties.

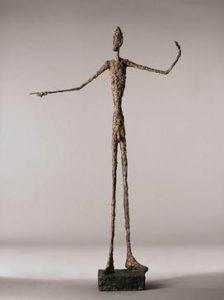

Giacometti’s uncertainties found their ultimate expression in his sculptures of pencil-thin, elongated figures. These are so attenuated that they almost disappear when viewed from the side. They are formed from an aggregate of inelegant lumps. They are vulnerable, bewildered, and alienated — existential man personified.

Giacometti disavowed any such intention. He claimed to be preoccupied with form, not emotional content. In a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, he emerges as an artist obsessed with process and the essence of representation.

Giacometti was Swiss but spent his creative life in Paris. His father was a post-impressionist painter. His mother was from an aristocratic family. An early self-portrait shows a handsome 19-year-old with fine, almost feminine features and a great mass of curly hair.

He had a natural talent and moved through styles with a Picasso-like alacrity. He sculpted the head of a young man in a beautiful classical style. He painted a self-portrait in a post-impressionist style. Another sculpted head has the blocky simplification of pre-Columbian art.

From there, it was on to cubism, a style that seemed to slow him down, where he found problems that held his interest. He translated the masses and contours of the human body into planes and facets, and in a sculpture of a woman’s torso, reduced the trunk and legs to three elegant planar columns that lock together like crystal rock formations.

Like other modernists, he saw a new language of form in African art. His first significant sculpture, the 1927 “Spoon Woman,” is dominated by an egg-shaped, concave form at its center. It has the primitive power of a female fertility figure.

Reduction, reduction, reduction. His 1932 oil portrait of his father is a struggle marked by negations, erasures, and backtracking. Like Cezanne and Picasso he hammered away at forms relentlessly. Unlike them, he left a record of his struggle. He scratched and erased, leaving thread-like lines intact on some edges, emphatic black slashes on others.

In the early 30s, he was a surrealist. He explored the menacing properties of forms. An abstract slab sprouts horns. Male shapes probe female shapes with long, spike-like projections.

The culmination of his surrealist phase was the famous “Woman with Her Throat Cut.” The subject looks less like a woman than an arachnid, a scuttling scorpion. Its segmented neck is nearly severed by the fatal cut.

The classic elongated figures emerged in the postwar years, seemingly out of nowhere. Were photographs of skeletal concentration camp survivors an inspiration? No one knows. Despite their attenuated forms, they aren’t frail or weak. They are giants anchored by huge pedestal feet.

In his drawings and paintings, Giacometti continued his research into reduction and representation, working strictly in monochrome so as not to complicate the issue. Many works have an intentionally unfinished quality. Having zeroed in on salient features of a subject, he would stop, not even bothering to put in a second arm, or the other leg of the table. In some, the search for the essence becomes so obsessive that the pencil tears through the paper.

In others, the eraser becomes an important drawing tool, and you can see him pulling elements out of the picture, like a scientist, to see just how much he can take away and still have the mind fill in the rest.

Toward the end of his life, battling stomach cancer, Giacometti seemed to take an opposite tack. The black, baleful heads he now drew were heavy with redundant lines, a mass of black threads winding round and round the form, like a spider wrapping its glassy-eyed victim.

Giacometti had a profound influence on the art of his time. The abstract expressionists carried forward his self-consciousness about process, until process became all and painting became about the act of painting. But he also influenced a generation of figurative artists who were looking for new ways to represent the human form and found inspiration in Giacometti’s messy essence.

Museum of Modern Art

2001