Jackson Pollock is to American art what James Dean was to American film, or Billie Holiday was to American jazz. He was gifted, moody, rebellious, and self-destructive. And like them, he died young (44) leaving us to wonder what direction he would have taken had he lived. He became, in short, a legend, and our fascination with him seems to grow with each decade since his drunken driving death in 1956.

Jackson Pollock painting with wife Lee Krasner in the background. Photo by Hans Namuth.

A controversial biography by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith won the Pulitzer Prize in 1990, but was criticized in art circles for seeming to exploit Pollock’s troubled personal life, including his alcoholism and bouts with depression. There has been no shortage of exhibits devoted to his work – including one a few years back of the drawings he did for his Jungian analyst, and a recent one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on his notebooks. But there has been nothing to compare to the current one at the Museum of Modern Art, which is the mother of all Pollock exhibits.

You know you’re in for an extravaganza of sorts when you encounter, in the hallway outside the show, listening stations, where you can don headphones to hear cuts from a CD of Pollock’s favorite jazz tunes. Not only does this exhibit have just about every major Pollock painting from every period in his career, but it has films of him tossing paint onto a horizontal canvas, a full-size reproduction of the shed-like studio in East Hampton,Long Island, where he made many of his late works, and an instructive display demonstrating how he achieved his various drip and spatter effects.

But this is also a show that tries to go beyond the Pollock myth, and to make a serious assessment of Pollock’s art. It carefully documents, gallery by gallery, every step in Pollock’s career, from his early representational works of the 1930s, through the surreal and totemic work of the early Forties, through the gradual development of his “all-over” drip style, to the late works, in which he confounded critics by re-introducing figurative images in his work.

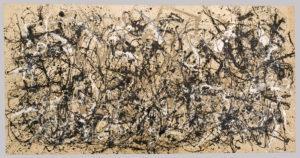

Ever since a 1949 Life magazine article asked “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” and Time nicknamed him “Jack the Dripper,” the general public has been scratching its head over this rough and defiant character, wondering whether art that looks so random, that looks as if “anyone could do it,” can truly be great.

That is the point behind the part of the exhibit that demonstrates how Pollock created his various effects: by dripping the paint from a brush or a stick, swinging a can with a hole in it above the canvas, or squirting paint with a turkey baster. The curators argue that Pollock exercised far greater craft and control than is generally supposed. To identify all the different lines that Pollock used, writes curator Kirk Varnedoe in the catalog, would require “perhaps as many words for ‘line’ as the Inuit legendarily have for ‘snow.’ ”

“Autumn Rhythm,”

No one denies that Pollock’s process left more to chance than most styles of painting. Some critics have compared it to the “automatic writing” of surrealism, in which the artist tapped into his unconscious, while others have found similarities to jazz, with its spontanieties and improvisations.

Indeed, metaphors involving dance and music repeatedly crop up in discussions of Pollock’s work, and ties in with the idea of abstract-expressionism as “action painting,” in which the painting is seen as the record of a kind of existential struggle or performance. This idea is underscored by the exhibit’s film of Pollock working on one of his large drip paintings. In it, we see the artist moving crab-like down the length of a horizontal canvas, cigarette in his mouth, rhythmically tossing paint from a can with a brush, almost like a priest dispensing blessings.

The show does a fine job of letting us see how Pollock’s style developed. His earliest works were representational, and influenced by his teacher, the outspoken regionalist artist Thomas Hart Benton. Even in these early landscapes, however, we can see Pollock’s moodiness, and more importantly, the visceral quality that is the strongest hallmark of his work; the hills and shrubs and trees all seem to be alive, to be erupting or surging upward.

Benton taught Pollock a method of analyzing the composition of paintings by abstracting the forms, and Pollock used this as an end in itself, as a painting style. In his early figurative works, the flesh of the bodies seems to writhe, to be enveloped by flames. Drawing on Picasso’s cubism, and Miro’s linear surrealism, Pollock’s work of the early Forties, such as “Birth,” incorporates body fragments, symbols, American Indian masks and totems in compositions that look like overflows from some Jungian collective unconscious.

As early as 1934, we see Pollock experimenting with totally abstract works, but it wasn’t until 1943 that he began to pour and drip in earnest. His classic all-over compositions were made between 1947 and 1950. Although there’s always been a tendency to lump these together as “drip” paintings, they do, in fact, have very different styles and characters. “Autumn Mist: Number 1, 1950,” for example, is constructed from such a dense web of delicate lines that it has a soft, enveloping quality. Others, such as the famous “Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950,” seem like expressions of an intense energy, as if one were peering into the realm of highly charged, subatomic particles.

In the end, it’s that emotional intensity that we value the most about Pollock’s art. His European counterparts seem cerebral by comparison. Pollock is the great American primitive, almost like an act of nature himself, a volcanic force. No matter what we think of his painting, there’s no mistaking the emotional intensity he put into it, the sense that every painting – to him – was a matter of life and death.