In the heady years after World War II, the country was ready for a celebrity artist. America had already produced every other kind of famous person, from movie stars to Nobel Prize-winning novelists. There even was a celebrity architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, but no truly famous artist. No one of the caliber of Picasso, or Matisse, or even the flaky Salvador Dali.

Then along came Jackson Pollock. A shy, brooding Westerner in jeans and a T-shirt, cigarette dangling from his lips. A real American, not one of those European aesthetes with their capes and berets. And he had this new way of painting. He put the canvas on the floor, and he flung the paint. Just let it spatter and drip all over the place in this wild energetic tangle. James Dean with a paintbrush.

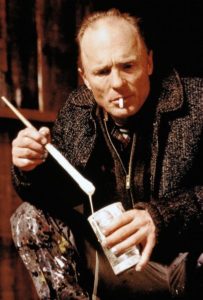

Ed Harris as Jackson Pollock.

Had Pollock been more like the egomaniacal Dali, or the supremely self-confident Picasso, he might have handled the role. Instead, he was unstable and riddled with insecurities. He was given to catatonic depressions, frenetic bursts of energy, and abusive, drunken binges. He needed approval desperately but couldn’t accept it when he got it and self-destructed in the pressure cooker of fame.

This is the story told in “Pollock,” starring Oscar nominees Ed Harris and Marcia Gay Harden and directed by Harris. At a time when biographical movies routinely distort and elaborate, “Pollock” does things the old-fashioned way. It tries to tell what really happened.

It succeeds in this regard more than the book upon which it is based, “Jackson Pollock: An American Saga,” by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, which, though exhaustively researched, went beyond fact into psychoanalytic speculations about Pollock’s sexual conflicts and his reasons for dripping paint (something to do with urination and potency).

The film gets the relationship between Lee Krasner and Pollock just right. Krasner, also a gifted painter, was probably the only person in Pollock’s life with whom he had a sustained, intimate relationship. She provided the constant emotional support Pollock required, and, with superior social skills and connections, pushed the buttons that made it possible for him to succeed in the New York art world.

Both Harris and Harden studied painting in preparation for their roles, and the film does a good job with studio scenes and conveying the milieu in which this new art evolved. When the movie begins in 1941, Pollock is still in his totemic style – a semi-abstract approach that was heavy on symbolic images – of animal heads, broken spears, birds, numbers, flames, and fragmented human figures. In one scene, Krasner surveys a new canvas (“Male and Female”), and though impressed, tells Pollock that his style conforms neither to the rules of cubism nor surrealism nor any of the other prevailing avant-garde styles.

In other painting scenes, we see Pollock struggling with a 20-foot-long canvas commissioned by dealer Peggy Guggenheim. As the story goes, Pollock had to knock down a wall of his apartment to make room for the huge canvas, but he let months go by without putting a mark on its white expanse. Finally, under intense pressure to deliver it, he painted the whole canvas flat-out in one day and night – a turbulent composition that’s been compared to a stampede of wild horses.

Almost as important to Pollock’s career as Krasner was the critic Clement Greenberg. Greenberg was as intellectually confident as Pollock was self-doubting, and he sometimes strayed from the critic’s role to that of guide and guru. Jeffrey Tambor captures the Greenberg arrogance, but makes the cerebral critic a bit too lugubrious. The film manages to convey the subtle point that even as Greenberg championed Pollock, the theories he put forward to explain the work didn’t always fit the art. Fortunately the theories were sufficiently esoteric that few people at the time noticed.

Although much of the discussion about the movie has centered on Pollock’s lousy character and his treatment of Krasner, his relationship with the media was just as telling and had more profound ramifications for American culture.

After a 1949 Life magazine article asked if Pollock was America’s “greatest living painter,” nothing was the same for Pollock, and American art. Pollock was photographed in front of a long horizontal painting, arms folded across his chest and legs crossed in a defiant pose, the trademark cigarette in his mouth. The American art world, formerly small and insular, had been annexed by the American media.

Soon, photographer Hans Namuth was filming Pollock in the act of painting. People wanted to see the artist doing his thing, and the film Namuth made, with its jazz soundtrack, raised Pollock’s star even higher. But it came at a price. In the movie, the imperious Namuth directs Pollock according to his idea of the creative process, or what its image should be. “Don’t start so fast,” he tells him. “Make it look as if you’re thinking.” After one such session, the insecure Pollock goes in the house, drains a couple of glasses of whiskey, and flips over the Thanksgiving dinner table.

By the end of the movie, Pollock had become that unique American creation: the celebrity who is famous for being famous. He was finished as an artist, and, filled with self-loathing, lapsed into drinking and womanizing.

But the lesson of fame was not lost on the next generation – the pop artists – who adapted much more readily to the new rules, none so successfully as America’s next art superstar, Andy Warhol.

2001