“Adam and Eve”

Anyone who’s done the European museum circuit knows the feeling. After you’ve seen your umpteenth “Holy Family,” or “Virgin and Child,” or “Adam and Eve,” with their stylized poses and gestures, your eyes glaze over and the emotions shut down.

That’s the surprise of the wonderful Jan Gossart exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gossart (ca. 1478-1532) was a Netherlandish artist who, through a fortuitous combination of temperament, influences and patronage, managed to inject life into worn-out themes.

How? In “Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart’s Renaissance,” Gossart does what great artists and writers alike have always done: re-imagined old stories with fresh psychological insight.

Take Adam and Eve. If you accept the Fall of Man as a metaphor for lost innocence or the birth of self-awareness, then the characters can be rendered as unfeelingly as the symbolic figures on a Tarot card.

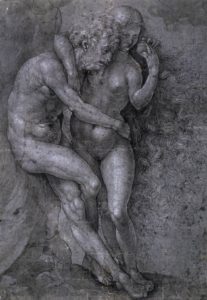

Gossart puts real, believable people on the narrow stage between the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge. Although two of his most ambitious Adam and Eve paintings were not loaned for this show, several drawings were and, as is often the case, they are even more daring than the paintings. You have never seen an Adam and Eve like the pair in Gossart’s 1520 pen-and-ink drawing from the Duke of Devonshire’s collection.

Adam is a man-sized figure but is anything but manly – a lank, pathetic figure who looks half drugged. He drapes himself on the much sturdier Eve, clinging to a shapely hip. She is no less surprising — a frankly sexual pubescent woman who is calmly in charge of this seduction.

Different in character, but no less original, is the “Adam and Eve” in brown ink from the Albertina in Vienna. This Adam, whose fig leaves indicate he’s already had his first bite, looks not so much ashamed as someone who’s dancing for joy. He could be doing a jig. There’s no hint of guilt in this couple’s readiness to get on with this knowledge-business.

How did Gossart end up doing pictures like this? In his youth, he belonged to an early 16th century scene called Antwerp mannerism, which made a virtue of peculiarity in religious compositions. Then, in 1508, Gossart went to Italy with his patron, Philip of Burgundy, where he picked up the Italian penchant for nude figures in biblical and mythological narratives. This meshed with his patron’s desire for eroticism in art.

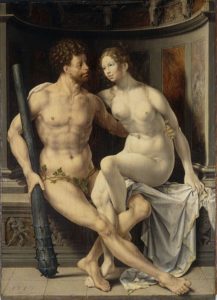

“Hercules and Dianera,”

So this show of 145 works, including 50 of Gossart’s 63 known paintings and 35 of his drawings, along with pieces by important predecessors and contemporaries, is filled with memorable couples. “Hercules and Dianera,” is probably the signature image of this show. As with Adam and Eve, love is their undoing, but tragedy is still far away (Hercules will later die as a consequence of infidelity). Gossart’s blend of the ardent and the peculiar is evident in the pretzel-like entanglement of the lovers’ legs.

Oddity wins out over the erotic in “Salmacis and Hermaphroditus,” a couple out of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” Salmacis is so maniacally intent on merging herself with the handsome Hermaphorditus that the gods grant her wish – literally. The two are turned into a mixture of male and female (one set of legs, two torsos) to the eternal shame of Hermaphoroditus.

Gossart brought his psychological realism to religious subjects, too. Never has Christ looked so disillusioned or earthbound as in Gossart’s paintings of the Passion. Then there is the dilemma of the aged Joseph in “The Holy Family.” Emotionally distant from the gay mother and the squirming baby, he looks straight out at us with an expression that can only be described as mystified.

The exhibit is arranged mostly chronologically. From Gossart’s trip to Italy, there’s a fine drawing of the Coliseum in which he revels in this romantic ruin with the plants sprouting from its crumbling walls.

The exhibit is arranged mostly chronologically. From Gossart’s trip to Italy, there’s a fine drawing of the Coliseum in which he revels in this romantic ruin with the plants sprouting from its crumbling walls.

The last gallery, which is all portraits, is a different sort of joy. These accessible paintings are a good introduction to the artist and are less challenging than the more imaginative subject matter. Who doesn’t know the pinched, mean faces in “Portrait of an Old Couple,” so self-righteous in their tight-lipped disapproval? In fact, it might be worth going through the show from back to front, starting with the portraits and ending with the mythical lovers.