John Ruskin (1819-1900) has often been called the greatest art critic ever, and for good reason. He wrote so well about art that he taught Victorian England (a distinctly literary culture) how to look at paintings. He rediscovered an architectural style – Venice’s Gothic stone buildings – that others had dismissed as barbaric. He championed a misunderstood artist – the highly original British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner – and made him a hero. And he nurtured a fledgling group of artists – the Pre-Raphaelites – who wanted to take art in a new spiritual direction.

He was equally at home in the past and the present, and his commentary ranged not just across the visual arts but into social, religious, economic, and even environmental issues. He was an authority on everything from Egyptology to clouds to the effects of mechanization on the human spirit.

In this, the centenary of Ruskin’s death at the age of 80, he is the subject of an important biography (“John Ruskin: The Later Years,” by Tim Hilton), a popular play about his disastrous marriage (“The Countess”), and an exhibit of drawings, manuscripts, letters, and memorabilia at the Morgan Library.

“The Countess” deals with the triangle that developed between Ruskin, his wife, Effie, and the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais, a scandal that rocked mid-19th century England. The playwright, Gregory Murphy, drew on letters from the Morgan Library that are on display in the current exhibit, “Ruskin’s Italy, Ruskin’s England.”

The exhibit covers Ruskin’s life from his upbringing as a precocious and indulged only child to his final decade, in which madness robbed him of his faculties. In between is Ruskin’s prodigious output – volume upon volume – and many illustrated with his own drawings.

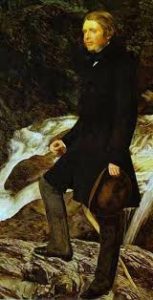

Portrait of John Ruskin by John Everett Millais

Ruskin was the son of Margaret and John James Ruskin. The father was a wealthy wine importer, the mother an evangelist. As a boy, Ruskin copied the illustrations from fairy-tale books, wrote poetry, and (reflecting his mother’s influence) wrote his own sermons and bound them into little books.

Ruskin played a major role in the Gothic Revival, arguing that medieval architecture was superior to that of his own day because the builders invested their handcrafted forms with symbolic meanings and spiritual values.

Sketchbooks filled with meticulous drawings of architectural details show the length to which Ruskin went to understand and document the architecture of Venice and other European cities. Ruskin’s wife wrote to her mother about her husband’s enthusiastic assault on Venetian architecture, describing him “climbing about the capitals covered with dust … or cobwebs.”

In “Modern Painters,” Ruskin championed Turner and defended him against widespread ridicule by the press. He praised his ability “to give the far higher and deeper truth of mental vision, rather than that of the physical facts,” as in “The Pass at Faido, St. Gotthard,” a watercolor commissioned by Ruskin that conveys nature’s power in water rushing over rock.

Of Britain’s more popular (and more conventional) landscape painter, John Constable, Ruskin wrote “I have never seen … any signs of his being able to draw,” though he decided that his “clumsy hand was honest, and his flickering sunshine fair.”

Ruskin became embroiled in a notorious lawsuit when he criticized one of James McNeill Whistler’s confections, “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket,” by writing that he “never expected to hear a coxcomb ask 200 guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler sued for libel, creating a sensation in London society, but won only a derisory award of a farthing and nothing for costs.

Letters describe Ruskin’s obsession with a young girl, Rose La Touche, casting light on his unnatural fascination with young girls (a trait he shared with another Victorian writer, Lewis Carroll). In the case of Rose, the middle-aged Ruskin waited until she was 20 before he unsuccessfully proposed marriage. A stunted emotional development was likely at the root of his marital problems. He fell in love with his wife, Effie, when she was 15, and married her five years later. But the marriage was never consummated.

Letters and memorabilia provide little clue to why he went mad in the 1870s. It may simply have been inherited. His paternal grandfather had succumbed to a melancholic madness before committing suicide.

A few brief notes from his periods of mental collapse are all the prolific writer left behind to shed light on this. In one he wrote, “The despair and awfulness of it [are] beyond anything conceivable by man – or God.”

Pierpont Morgan Library

2000