Let me tell you about this cool dream I had. These men were playing cricket in some sort of park, except the trees in the park looked like giant stair spindles. When the batter hit the ball, a giant sea turtle flew over his head. Except the turtle’s head was a smooth cylinder. And there was a woman in a box with a gag — or maybe a surgical mask–over her mouth…

Let me tell you about this cool dream I had. These men were playing cricket in some sort of park, except the trees in the park looked like giant stair spindles. When the batter hit the ball, a giant sea turtle flew over his head. Except the turtle’s head was a smooth cylinder. And there was a woman in a box with a gag — or maybe a surgical mask–over her mouth…

Okay, I confess. This isn’t really my dream. It’s a description of a painting called “The Secret Player” by Rene Magritte, who once said: “Surrealism claims for our waking life a freedom similar to that which we have in our dreams.”

The point I’m trying to make is that most people find their own dreams fascinating, but are bored with those of others. Why? Because most dreams (excepting the occasional Freudian one) are indecipherable and mostly meaningless — especially to outsiders. This poses a challenge for any artist who wants to use dreams as a template for art.

I thought of this at the outset of the Museum of Modern Art’s new show, “Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938.” The show is about Magritte’s formative – and most creative – years. This is when he did many of his most famous paintings: the lovers with draped heads, the pipe that is not a pipe, the shoes with toes, the half-woman, half-fish.

“The Secret Player” comes from the first half of this show, when Magritte –a conservative artist by surrealist standards – was at his most florid and bizarre. These are the ones that dare you to make sense of their plots. In the elaborately staged “The Menaced Assassin,” a businessman stares dully into a gramophone horn while the nude and bloodied corpse of a woman lies on the divan behind him. Armed men in bowler hats stand in the wings, ready to rush in, while three other men peer in from the balcony. All are disengaged, as if in a trance.

Magritte gradually settled into his signature style – a plain and meticulous realism. No matter how outlandish the subject, he painted it in his matter-of-fact way. Thankfully, he also gave up narrative. In the show’s second half, there are no more plots to puzzle over. His paintings became droll one-liners, snapshots of the weird and the impossible .

A man stands with his back to us, looking into a mirror, but instead of seeing his face, we get the same view of the back of his head. In “Clairvoyance,” a still life painter contemplates an egg and paints a bird in flight. In “The Portrait,” a slice of meat on a plate looks up with a human eye.

He liked playing games with the female nude. In one, the artist in the picture paints a real woman into existence, the brush giving her flesh and form. “The Eternally Obvious” is a suite of five paintings, each a partial view of a nude, but arranged vertically so as to form an almost-complete figure. “Collective Invention,” reverses the usual mermaid convention, putting the fish part on top, with the woman’s legs on the bottom.

Magritte turns philosophical about reality and representation in “The Treachery of Images, which looks like a simple illustration of a tobacco pipe, but with a caption that reads “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” French for “This is not a pipe.” In other words, it’s not a pipe, but a painting of one, the kind of trope that would become a staple of conceptual art.

The show ends with the onset of World War II, after which Magritte never regained his creative edge. He did variations on familiar themes but he lived long enough, dying in 1967, to see his fame take off with the pop art frenzy. His personal image as the “the ordinary man in the bowler hat, suit and tie,” struck a chord, as did the painted images of such men coming down from the sky holding their umbrellas.

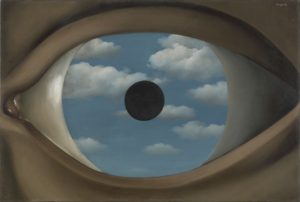

His images were snatched up for commercial purposes. The floating eye of his painting, “The False Mirror,” became the basis for the iconic CBS logo. A museum show a few years back showcased no fewer than 60 book covers with Magritte imagery.

I doubt his surrealist friends from the 1920s would have approved (the fame-obsessed Salvador Dali excluded). But the MoMA stops short of all this. Its subject is a young between-the-wars artist who painted daringly bizarre imagery, who at first immersed himself in incomprehensible dreams.

In the course of the show, he gradually wakes up. He polishes up his messy material. What was once disturbing gets punchier and funnier. He made incomprehensibility the point and let the audience in on the joke. They have loved him ever since.