Man Ray poses an interesting challenge for an institution like the Jewish Museum: how to frame an exhibit about a Jewish artist who, throughout his career, denied his Jewishness?

Few people know that the famous avant-garde artist and photographer was born Michael Emmanuel Radnitzky to Russian Jewish immigrants. Ray, who spent most of his adult life in Paris, cast aside not only his Jewish identity, but also much of his American one, disappearing almost entirely into the role of a European dadaist and surrealist.

Rather than sidestepping a seemingly uncomfortable issue, the Jewish Museum has put it front and center, titling the show “Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention” and making Ray’s enigmatic, contradictory persona its focus.

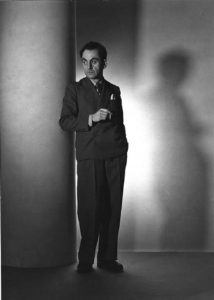

Few artists have been so simultaneously narcissistic and self-effacing. His self-obsession comes across in all the self-portraits he did in different media – from photographic to sculptural to abstract to conceptual. If there’s a signature image to this show, it’s his 1933 “Auto Portrait,” a wooden box containing a bronze cast of his face cushioned by crumpled newsprint. He looks out defiantly as if enduring the indignity of popular opinion.

It’s an odd stance for an artist who delighted in surrealist tricks and for whom being misunderstood might be considered part of the game. But Ray had his own mixed feelings about himself and his work, especially his role as a photographer. He alternated between calling it an art form to dismissing it as purely a mechanical process. He resented his financial dependence on commercial work, but take a look at his self-portrait as a big-time fashion photographer. He’s scowling, as always, but clearly enjoying the power.

The more his fame as a photographer grew, the more he insisted that he was really a painter, but it’s hard to find a painting in this show that doesn’t look like it’s by someone else, whether Picasso, Matisse, Marcel Duchamp or Giorgio de Chirico. As for the surreal objects dutifully included here, such as the flatiron with the nails or the metronome with eye, they have lost much of their potency through over-familiarity – a problem for any art form too reliant on surprise.

But Ray was a great photographer and shouldn’t that be enough? He arrived in Paris at the perfect time (1922) to do portraits of such literary greats as Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and the dying Marcel Proust.

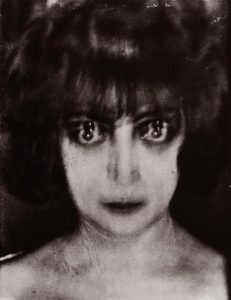

There are also portraits here of two of that period’s most fascinating women, Kiki of Montparnasse and the American photographer Lee Miller, both of whom were lovers. Kiki — model, actress, singer, artist – is the owner of that nude back on which Ray superimposed the F-shaped holes of a cello.

His greatest innovation was his so-called “Rayograph,” or cameraless photograph, in which objects were placed directly onto print paper, creating dreamlike abstractions of hands, combs, coils of string and other ordinary things.

Sometimes there was cross-fertilization between the society portraits and the artistic work, as when he accidentally double-exposed the face of one of his subjects, the Marquise Casati, giving her two pairs of eyes. The marquise loved it so much that she ordered dozens of prints and sent them all over Paris.

An early gallery is devoted to work Ray did between 1912 and 1915 when he lived in an artist colony in Ridgefield Park, N.J.. There, he and his companion and later wife, poet-painter Adon Lacroix, were part of a small bohemian community.

At the time, Ray was doing serious Cezanne-like and cubist landscapes, but a better indicator of his future was the dadaist journal he and Lacroix collaborated on. It consisted of only four pages and the issue shown here, number O, was the only one they ever did. They called it The Ridgefield Gazook and the front featured a scratchy pen drawing of two copulating grasshoppers.

Hidden among the stick-like legs, you can just make out the letters that spell “Man Ray.” It was a strategy of concealment that he would pursue for the rest of his life.