Visitors to“Marsden Hartley’s Maine” at the Met Breuer are greeted by a wall-size video of waves crashing against a rocky shore. It’s a fitting evocation of the quality of Maine that has fascinated artists for 150 years: stark and rugged beauty laced with a touch of menace.

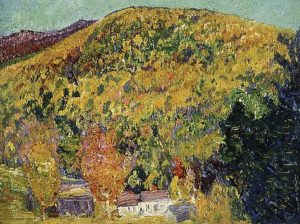

“Robin Hood Cove”

The parade of artists who went to Maine is like a who’s who of American art: Winslow Homer, Frederic Church, Robert Henri, Rockwell Kent, George Bellows, Childe Hassam, John Marin, Edward Hopper and all three Wyeths. But only one, Marsden Hartley, was a true native.

In what is hands-down the best show in New York right now, the Met focuses on this immensely gifted artist who was as cosmopolitan as any American, who absorbed every lesson modernism had to teach at the turn of the 20th century, and whose paintings were often saturated with the look and feel of New England’s northernmost state.

Born in Lewiston, Maine, in 1877, he had a hardscrabble childhood marked by death and abandonment. Somehow he developed into an artist — then got himself to New York. There he emerged as the best of the group that grew up around photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his 291 Gallery — formidible company that included Arthur Dove, Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Paul Strand.

In 1912, he went to Paris and Berlin. There he developed a variation on cubism that looks like collage — flat overlapping patches in which numbers and symbols communicate like words in a poem. He returned as World War I heated up, came back to New York and spent the next two decades painting, writing poetry and exhibiting his work to positive reviews.

With the Great Depression came the rise of American regionalism, a realist style that focused on the charm and authenticity of small towns and rural landscapes (think Wood’s “American Gothic). Hartley, despite wide-ranging talents, had never nailed down a clear artistic identity. It seemed to bother him that artists “from away,” were claiming his homeland’s rocky shores, fir-covered islands, and forbidding forests.

In 1937, he announced that he was returning to be “a painter of Maine.” His life had come full circle.

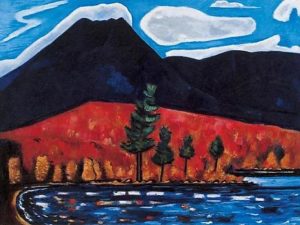

“Summer.”

The Met Breuer show is organized chronologically, beginning around 1906, with landscapes of mountainous scenes along Maine’s western border. These are in a post-impressionist style that was almost as systematic in technique as Seurat’s pointillism. Unlike Seurat’s calm compositions, though, Hartley’s mountains vibrate with electric color and threaten to push the strip of sky right out of the painting.

Many American impressionists made entire careers out of paintings like these, but Hartley was already restless and eager to push on. He began to build his paintings out of strong, simple shapes like those in Japanese prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige, six of which are shown here next to his paintings.

The romantic, visionary works of Albert Pinkham Ryder were another influence. From Ryder he acquired a love of night scenes with clouds in stark zig-zag patterns. He painted dark mountains with gut-twisting forms that are more visceral than visual.

“Evening Storm, Schoodic, Maine.”

He developed a faux-primitive side and painted clouds as a child might — as big awkward blobs that float like blimps or levitating rocks. Inspired by Homer’s pictures of the heaving, roiling ocean, he painted the crashing surf, but in his faux-primitive style. These didn’t always work. His big sprays of surf look static, like pillars of ice.

For almost a century, Hudson River School painters depicted nature as awesome and frightening. Hartley has some of this in his art, but he was a modernist not a 19th-century realist. Imagination was his god. Even when he painted that quintessential Maine subject, a lighthouse, it tilts nightmarishly.

There’s a gallery that touches on Hartley’s gay side, a theme that played a major role in earlier cubist works, not shown here, that were elegies to a German officer he’d loved. Coming out was never an option for Hartley, but he expressed his desires in paintings of absurdly muscular near-nude men who were ostensibly lumberjacks or fishermen.

“Autumn”

After a cosmopolitan life in Europe and New York, life in Maine had its social hardships. Hartley was in his sixties when he came back. He grew bitter and felt insufficiently appreciated (which he was). His paintings feel like laments — both metaphorical and literal– as in the pictures of bleached log piles he called “Ghosts of the Forest.”

There’s a mood of acceptance in his late pictures of Mount Katahdin at twilight. The mountain no longer heaves up violently, but sits calmly in the background. In one of these, set in November, the foreground presents a single green conifer on the shores of a quiet cove. It’s hard to not to see this solitary tree as the artist, a genius who never found personal happiness and whose heart gave out the following year – 1943 – at the age of 66.

June, 2017