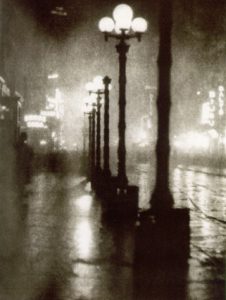

“Broadway at Night,” by Alvin Langdon Coburn

It’s one of the great marriages of motif and medium: nighttime and black-and-white photography.

Because the world turns colorless at night, and because detail is suppressed, a nocturnal photograph in black-and-white film is less of an abstraction from reality than a daytime photograph. Aside from being flat, a black-and white photograph of a tree silhouetted against a silvery moon contains all the information that the eye would pick up. What you see is what you get on the print.

“Night Vision: Photography After Dark,” at the Metropolitan Museum, explores this alluring, dimly lit art-historical corner with 40 works from its collection by such 20th-Century masters as Berenice Abbott, Brassai, Bill Brandt, Robert Frank, Andre Kertesz and the New York tabloid photographer Weegee.

Night photography didn’t really exist until the late 1880s when the gelatin dry-plate process reduced exposure times significantly. Coincidentally, there was already a well-developed noctural pictorial model to draw on in the late-19th century tonalism of painters like George Inness, Ralph Blakelock and Alfred Pinkham Ryder.

You can see this painterly influence in a print by Edward Steichen, who originally trained as a painter and whose “Woods Twilight, 1899” owes much to the misty insubstantiality of Inness’s late work.

Nighttime photographers said goodbye to the landscape pretty quickly, however. Once the 20th Century got under way, it was the city, with its cobblestones, shadowy alleys and glittering avenues that captivated the imaginations of these photographers.

Alvin Langdon Coburn, a contemporary of Stieglitz and Steichen, was enchanted by New York’s new electric arc lights. In “Broadway at Night,” he sought to capture the magic of the lights going on, like “a stringing of pearls” from 26th Street up to the great hotels at 59th.

Aided by the technical innovations of smaller handheld cameras, faster film, and flashes, legions of photographers explored the moods of the world’s great metropolises. The Parisian photographer Brassai was one of those who helped popularize the noir aesthetic, a recipe that required not only darkness but wet weather.

“Fog and rain…tend to soften contrasts,” he wrote. “Steam, as well as wet ground, act as reflectors and diffuse the light of the lamps in all directions. Therefore, it is necessary to photograph certain subjects in the rain, since it is the rain that makes them ‘photogenic.’”

The deep dark of Brandt’s “London by Moonlight: St. Paul’s,” was made possible by the blackouts imposed during the London Blitz, of which he wrote: “The darkened town, lit only by moonlight, looked more beautiful than before or since. It was fascinating to walk through the deserted streets and to photograph houses which I knew well, and which no longer looked three-dimensional, but flat like painted stage scenery.”

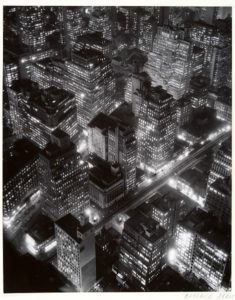

“Nightview, New York,” by Berenice Abbott.

Abbot was famous for her photographs of New York City skyscrapers, in which light glitters from within dark, boxy shapes, the way embers glow within a blackened fireplace log. To maximize the effect in “Nightview, New York,” she shot the picture in the darkest days of December, between 4:30 and 5 p.m., before people began to leave their offices and turn off the lights.

Noirish pictures far outnumber happy ones in this show. One of the few truly joyous ones is Sid Grossman’s “Mulberry street” of 1948, which captures the revelers and the kaleidoscopic lighting in Little Italy’s San Gennaro festival. Diane Arbus prowled the same festival a decade later, and found in it her usual freak show, including “Little Man Biting Woman’s Breast, N.Y.C.”

But Arbus’s photography doesn’t really rely on night for its impact. The same is probably true of Weegee, whose “Human Head Cake Box Murder,” of 1940, would probably have been just as horrible were it photographed in broad daylight – maybe more so.

John Cohen’s “Tenth Street at Night,” an abstract composition of rooftop, building edges, and windows could easily be an image from 1910, but is actually from 1960.

It’s one more demonstration of the illusory power of night photography in a show that pays well-deserved tribute to photographers drawn to the dark side.