There have been lots of different Patersons. The Paterson of Silk City millionaires, the Paterson of hopeful immigrants and rebellious strikers, the street corner Paterson of Lou Costello.

Joe Ruffilo and Don Kommit come out of the Beatnik Paterson, the Paterson of Allen Ginsberg, of saxophone solos in basement coffeehouses and truckloads of abstract-expressionist paintings evoking the Great Falls.

Joe Ruffilo, Paterson artist.

These two artists have been part of every wave of hipness that has swept Paterson in the past 40 years. Today, they are looked upon as bohemian patriarchs, the ones who know how to find a loft or other cheap housing, where to buy art supplies or a guitar string, and, probably most important, how to keep going, how to keep being an artist, no matter what.

Countless coffeehouse pals must have long ago moved out to split-levels in Elmwood Park or Wayne, while these two continue to paint and sculpt and to draw inspiration from the bittersweet charms of their native city. And so, when they began reflecting on a theme for their current two-man show at the Paterson Museum, the word “progenitor” popped up.

“I don’t know who said it,” said Ruffilo, a loquacious guy with a goatee and horn-rimmed glasses. “But we decided it fit us.”

Don Kommit in 2017.

“We liked the definition, so we put it on the show announcement,” said Kommit, smaller, also bespectacled, and with a near identical goatee.

Hence, “Pair of Progenitors,” on a double bill with a show about motorcycles. The motorcycles are sort of relevant, evoking that Fifties and Sixties spirit of rebellion – “The Wild One” and “Easy Rider” – that was progenitor to these progenitors.

Ruffilo, in particular, slides easily between these two worlds. Before he was a serious artist, he was a motorcycle and car guy, “a gear head,” he says. His sculptures were made from scrap metal and machine parts salvaged from the floor of the race car fabricating shop where he worked. “I just started picking them up and making things out of them,” he said.

The result is very Patersonian, evoking the machine-soul of this city that once churned out entire locomotives. Unlike some metal sculpture, Ruffilo’s pieces don’t take unfair advantage of their ironness, don’t try to intimidate with jutting beams or huge slabs leaning in your direction. Ruffilo sculpts half-inch-thick steel as if he were making paper dolls – snip, snip, snip – and decorates the jigsaw-like pieces with curlicues of welding bead. He makes sure that each assemblage stands up neat and straight, like children dressed for Sunday school. Although essentially abstract, recognizable forms emerge: a sea horse, one of Da Vinci’s war machines.

Kommit is known for his constant sketching of city scenes. Many of his works look like sketchbook pieces that have been worked over with layers of paint, collage, and lines of poetry until they take on the weight and presence of easel paintings.

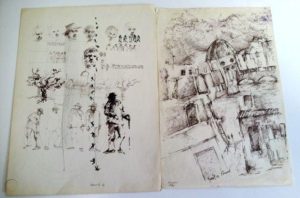

A page from the notebooks of Don Kommit.

His “Once More a Renaissance” is a collage of business cards, show announcements, stationery, poems, and painted vignettes built on a foundation of old-fashioned wallpaper. When he starts to explain about the Straight Street shop that supplied him with wallpaper sample books, and the people that worked there, doors swing open into Paterson’s past.

His art is a rambling journey. There are artists who you can sense are bored stiff, who may be entertaining, even moving, to the viewer, but who have disappeared behind their talent, forgotten how to keep themselves interested. Kommit doesn’t make that mistake. With him, the finished artwork and the journal of its creation are the same exuberant experience.

And, it’s all one long love poem to Paterson. Despite being a city whose glory days were over before Kommit was born, a place that seems unable to catch up, to make one of those renaissances that other cities have, Kommit sees only its greatness.

“It’s got all those things that great cities have: It’s got beautiful architecture, it’s got a castle on a mountain, it has a river coursing through it, it has parks and neighborhoods, and it’s got people from all over the world.” He rests his case.

Ruffilo and Kommit have watched all these bohemian waves wash over Paterson: the rock musicians, the hippies, the poets, the performance artists, the black activists, the jazz musicians, the painters, the students from William Paterson. They’ve seen it all, heard it all, been there, done that, and yet, they don’t seem the slightest bit cynical or world-weary. To listen to them, they enjoyed every period, picked up on the energy of every scene, reveled in La Boheme.

There were the open-mike nights at the readings of the Silk City Poets. And there was that artist center in an old church that ran a respectable program till the grant money ran out and, in Ruffilo’s words, “the rabble took over” – meaning them – and kept it going without heat or hot water.

“As long as we were carrying on programs in there, the city wouldn’t kick us out,” Kommit recalls.

Ruffilo’s face lights up. “Remember Dial-a-Poet?”

“We had a number on the wall,” Kommit explains. “People could call it and get a poet – one of us.”

“It didn’t last,” Ruffilo adds.

And now, here they are. Several marriages under their belts. Several sets of kids. They are beyond issues of success and failure. The important thing for them hasn’t been the objects left behind, but living and feeling things fully, being on, plugged in, alive and even a little feverish, heeding the call of Ginsberg’s “Howl.”

But the scene has changed. The new people seem to lack the bohemian spirit. Kommit and Ruffilo can’t put their fingers on it, but they both mark the decline to the advent of artist housing, to the city’s deliberate attempt to cultivate an arty image by fixing up the old mill buildings.

The gentrification it was supposed to spark never happened, and the spontaneity of the old scene was lost. Too many of the new artists don’t have any connection to Paterson, says Kommit, who himself lives in one of the subsidized lofts.

Ruffilo and Kommit find this beyond imagining, not feeding on the soul of the city. “We’re a product of the city, and what we did with our art is a product of that,” says Ruffilo.

In fact, it’s been said that only a city can produce a great artist, because only a city can reveal the full range of the human condition, can test ideas, provide so much energy and so much history. Think Joyce’s Dublin, Dickens’ London, Dante’s Florence, Miller’s New York, Picasso’s Paris. An artist without a city is like the sound of one hand clapping.

The Paterson Museum

2000