It’s almost unheard of for a single artist to be the subject of two concurrent exhibits at New York City museums, unless, of course, that artist is Picasso. Picasso can stand up to that kind of attention. He was amazingly productive, worked full tilt till he was 91, and went through phases, styles, and media like no other artist. In recent years, we’ve seen him invent cubism, seen a huge show devoted to his portraits, and seen another one that singled out his “weeping women.”

Currently, the Guggenheim is showing his work from the “War Years,” and the Metropolitan recently opened “Picasso: Painter and Sculptor in Clay,” the first such exhibit devoted to the artist’s work in ceramics. Interestingly, the two exhibits connect chronologically: The ceramic show picks up where the “War Years” show left off, but couldn’t be more different from it in character.

The paintings he made in Nazi-occupied Paris are gray, claustrophobic, and menacing. But after the war, he kicked up his heels and moved to the gorgeous Mediterranean coast in the south of France. Though he was 65, he took up a new medium, fell in love, fathered two children, and had some of the happiest years of his life. The ceramic work he made from 1947 to 1962 is gay, playful, and celebratory.

The paintings he made in Nazi-occupied Paris are gray, claustrophobic, and menacing. But after the war, he kicked up his heels and moved to the gorgeous Mediterranean coast in the south of France. Though he was 65, he took up a new medium, fell in love, fathered two children, and had some of the happiest years of his life. The ceramic work he made from 1947 to 1962 is gay, playful, and celebratory.

Picasso began to work with ceramics after visiting the Madoura pottery workshop in Vallauris, where the mineral-rich soil has supported a ceramics industry since Roman times. In the beginning he simply decorated plates and other ready-made objects turned out by the workshop.

The roundness of a plate seems to call for a face, and Picasso did a variety of these, a bearded faun with a maniacal grin, a noble matador, a smiling woman. Getting a bit more playful, he filled the plates with food, both painted and sculpted, creating works that look remarkably like Claes Oldenberg’s pop art: a pair of rubbery-looking fried eggs and a length of sausage, a fish and a wedge of lemon.

Some pieces make reference to the Greek vases that Picasso admired, but even here, his versions seem like irreverent knockoffs, cartoonish versions of the elegant black figures that the Greek artists drew against terra cotta backgrounds. Picasso’s are loose, improvisatory, almost like Oriental brush paintings. He tosses off some acrobatic figures with seemingly casual strokes of the brush that are, nevertheless, right on target. Picasso the joker surfaces in his manufactured fragments of antique pottery with profiles of himself and his then-current love, Francois Gilot.

Picasso never became an accomplished potter. He made pots of his own, but for the more ambitious pieces, the large, curvaceous bottles and animal-shaped vessels, he relied on master craftsmen who worked from his designs.

Preparatory drawings show how Picasso worked out abstractions of animal forms simplifying the rhomboid bulk of a cow, finding the geometry and oddities in birds and fish.

Although the clay of the Vallauris region was red, Picasso – accustomed perhaps to the white of the canvas – preferred white clay imported from elsewhere in France. On some of these, like the round-bodied, loop-tailed, long-necked “Bird,” of 1947-8, he made a bold pattern of zebra-like stripes, its abstracted form and joyful patterning suggestive of African wood carvings.

Perhaps because he didn’t feel this kind of work was destined for the museums, Picasso indulged his childlike side. The vessel titled “Head of a Woman Resting on Her Hands,” in which the woman’s eyes are crowded up at the top of her pear-shaped head, looks like a refugee from Sesame Street. No less silly is the rotund, mustachioed “Man in a Suit,” whose arms serve as the double handles of the vase and make him look as if he’s covering his ears in a hear-no-evil gesture.

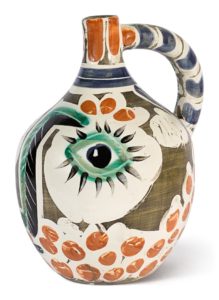

Throughout this show are jokes like these, cartoonish, happy faces smiling up at us from the bottoms of pots, or a pouring spout turned into a gaping mouth, or a curvaceous handle that turns out to be a friendly, smiling snake.

Is this really the great Picasso, we ask ourselves, in confronting two angry eyes staring out from a blotchy, finger-painted visage titled “Face of a Crayfish”? Or that flesh-colored torso-shaped vase on which the artist has incised a bellybutton and dressed it in a yellow bikini. Or those pots that seem to tip back on their heels, thrusting out their phallic spouts. Or the six-handled pot that looks like a giant tick, its sharp little claws resting on its swollen belly.

Every once in a while Picasso reminds us that he is, in fact, Picasso, and does some elegant bit of drawing, as in the wonderful bullfight scenes on oval plates, in which we see the sunlight and shadow in the ring, the crowds that surround, the bull, the picadors, the matador – everything – all done with seemingly casual dabs of color.

This is a show about the sheer pleasure of creating. Yes, there is something to be said for artistic suffering and soul-baring – we wouldn’t love a happy-go-lucky Vincent van Gogh nearly as much as we love the tormented one – but it’s nice to see an artist enjoying himself.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1999