As a painter of illusions, Pablo Picasso manipulated form in every possible way. He reduced reality to diagrams, fractured volumes, flattened space, and rearranged the features on the faces of his subjects.

It shouldn’t surprise that he’d be drawn to sculpture, where he could get his hands on the very stuff of matter and bend and twist to his heart’s content.

And so he did, as can be seen in an entertaining, sometimes goofy, sometimes dazzling show at the Museum of Modern Art, “Picasso Sculpture.” Here, heroic classical heads coexist with lumpy figures out of a Tim Burton Claymation movie.

One reason you don’t see many Picasso sculptures is that the artist hung on to them, keeping them in his studio like familiars or totemic ancestor figures. After he died in 1973, most went into the founding collection of the Musee national Picasso-Paris. With loans from there and other collections, MoMA curators have come up with 140 works created between 1902 and 1964.

If cubism’s impossible spatial relationships give you claustrophobia, you may find relief in a three-dimensional piece like “Guitar,” where planes are broken up but the laws of physics prevail. There’s something endearing in this humble cardboard and string construction, as if the great master were making something for a school art fair.

Picasso’s dealer, Daniel Kahnweller, called his wire constructions “drawings in space.” Some have the elegance this suggests. Others look like tangles of coat hangers. Better are the sturdier welded-metal sculptures. One of these, “Woman in the Garden” from 1930, is a knockout. It was the last of Picasso’s five unsuccessful submissions for a memorial to the poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

This is a truly lovely abstraction. A breeze lifts the woman’s hair and bends the stems of the two oversized flowers. Botanical forms mix with physical ones so that the woman’s torso arches like an unfolding leaf. The whole of it is painted white, which softens the coldness of the steel. Its only weakness is that it needs to be viewed face on. From the back, it looks like a stage prop held up with struts.

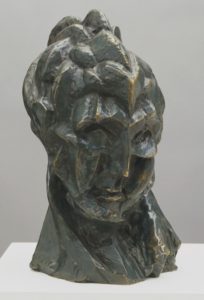

It’s a comical jolt to go from this lyricism to the bulbous-faced sculptures Picasso made at the Chateau de Boisgeloup in the early 1930s. Suddenly, you are in the realm of Mr. Potatohead, and an adults-only Potatohead at that. In these Freudian-surrealistic works, women’s noses resemble drooping phalluses. Other sexual puns abound.

It’s probably a mistake to give such tangible shape to Freudian theory. But Picasso was having fun with the big-nose look, and played around with it in other pieces, including “Head of a Warrior.” This is a reference to ancient sculptures of noble soldiers wearing crested helmets. But Picasso’s cartoonish warrior has bug eyes and the schnoz of a proboscis monkey.

Historians like to point to all the odd materials that Picasso used in this piece, such as the plastered-over tennis balls for the eyes, a crowbar lodged in its neck and a piece of industrial pipe to help prop it up. There’s a performance aspect to this. The Picasso mystique cast him as a wizard who could pick up an ordinary object, combine it with another thing, slap some clay on it – and – voila! – a work of art. A few decades later, he would combine a bicycle seat and handlebars to make the head of a bull.

Picasso’s situation in World War II was very strange. He had been labeled by the Nazis as one of the foremost of the “degenerate” artists. He had also painted “Guernica,” an attack on fascist atrocities in Spain. And yet, in an act of resistance, he stayed on in occupied Paris where he might have expected persecution and where he couldn’t exhibit. Either he had a protector or the Nazis decided not to make a martyr of such a famous artist.

From the war years comes the grim “Death’s Head,” a charred human skull and “Man with a Lamb,” a sorrowful masterpiece in which human stoicism is belied by the bleating lamb the man holds in his arms.

In the hands of another artist, the lamb might have seemed too cloying, but Picasso had a genius for rendering animals vividly and unsentimentally. That can be seen in “The She Goat,” a bronze which usually occupies MoMA’s garden. She is graceless and ungainly with her scrawny neck, sloping back, swollen udders and bulging sides. And yet, she possesses amazing dignity, even a touch of heroism, standing foursquare, as if silently proclaiming “I am here!”

With this piece alone, Picasso would have left his mark on Western sculpture.