From the album “River-Views, Bays & Sea Coasts” of William Gilpin

Unless you live in the country, you’re hardpressed to find a square foot of land that hasn’t been altered by humans. Even the land considered “natural” – that which hasn’t been covered by buildings, asphalt, concrete, gravel or astroturf – is probably the result of human design. In a typical suburb, the tree-lined streets, the lawns that surround the houses, the parks that provide refuge – were all someone’s ideas.

Where did those ideas come from? Answers can be found at “Romantic Gardens: Nature, Art and Landscape Design” at The Morgan Library & Museum. It finds the roots of our landscape aesthetics in the period between the mid-18th and the mid-19th centuries – the age of Goethe, Beethoven, Delacroix, Wordsworth, Emerson and Thoreau.

Shifting views of nature first found expression in landscape design for private estates in England, France and Germany. Later, those ideas traveled to America with the great public parks of Frederick Law Olmsted.

Before the Romantic Period, landscape design was driven by the French formal style, with its tightly organized paths and beds defined by geometric lines — nature disciplined to within an inch of its life.

The Garden at Versailles in a painting by Willaim Callow.

Cracks in the formal style appeared in the 16th century, when the high-keyed emotion of the baroque found its way into garden design. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s redesign of the gardens at the Villa d’Este at Tivoli transformed an orderly waterfall into a spectacular cascade over rough-hewn boulders.

By the time painter Jean-Honore Fragonard visited a century later, these same gardens had fallen into decline. But his watercolor of broken balustrades, billowy foliage and scraggly branches, highlights another feature of the Romantic aesthetic – its fondness for crumbling ruins overgrown by rampant vegetation.

Rushing water was also a hallmark of Chinese garden design, which reached Europe through reports and engravings of the gardens at the emperor’s summer palace. British writers praised its pleasing irregularity and “artful confusion.”

The Twickenham gardens of English poet Alexander Pope were celebrated for a three-chambered grotto that featured artificial stalactites and sparkling mineral-studded walls.

Soon, three ideals of landscape aesthetics were vying for primacy: the pastoral, the picturesque, and the sublime.

Architect Capability Brown, an advocate for the pastoral ideal, reorganized rich men’s estates into pleasing compositions of curling paths, gently rolling meadows, irregular clumps of trees and placid lakes.

At the opposite end of the continuum was the passion for nature’s wild and primitive force, the aesthetic concept that philosopher Edmund Burke called “the sublime.” A watercolor by J.M.W. Turner, “The Pass at St. Gotthard, near Faido,” captures nature’s wild side with a scene of violent, roiling rapids.

The “picturesque” was popularized by travel writer William Gilpin. He taught people to analyze nature like a painting, appreciating its planes, color and patterns of light and dark. Jane Austen satirized this fad in Northanger Abbey when her heroine muses on a walk: “It seemed as if a good view were no longer to taken from the top of a high hill, and that a clear blue sky was no longer a proof of a fine day.”

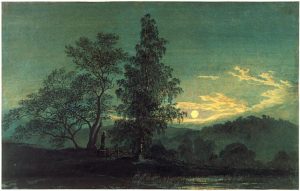

“Moonlit Landscape” by Caspar David Friedrich.

Beauty and sublimity merged in the almost mystical landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich, whose protagonists gaze into vast panoramas. The aristocrat Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Puckler-Muskau brought some of this spiritual longing to the design of his 1,500-acre estate, a project that went on for 30 years and which he once attributed to his “parkomania.”

Puckler-Muskau influenced America’s great park designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, who also drew inspiration from the Hudson River painters, a school that celebrated the sublime in America’s great wild landscapes. To get a sense of what an amazing creation Central Park was, be sure to look at the before-photographs of this dreary landscape contrasted with the proposed after views painted by Vaux. It looks like an impossible fantasy, yet in them you can easily recognize today’s Mall and boating lake.