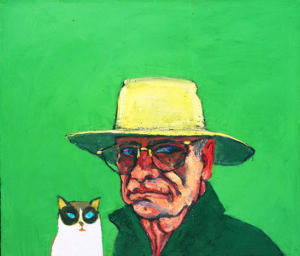

Paul Georges

The post-war generation of American artists came of age at a time when abstract painting seemed an irresistible force. Most were swept up by its vortex, but a tiny minority felt confined by a new orthodoxy and rebelled. For them, paint itself was not enough. They wanted to make pictures.

Now, with most of these artists dead or in their twilight years, the National Academy Museum has mounted “See it Loud: Seven Post-War American Painters.”

What makes these painters different from representational painters of the past, and what gives this show its special flavor, was their attempt to reconcile these two different modes of painting – the abstract and the representational.

Take Paul Georges, one of the outspoken leaders of the group. For him, picture-making didn’t mean a return to careful academic methods. His execution retained all the swagger and dash of action painters like Pollock and de Kooning. No subject seemed too daunting for Georges. He painted allegories and gods cavorting in the heavens. In a monumental canvas that greets visitors to this show, a Zeus-like figure (with the artist’s face) yanks a maiden off a flying horse. Despite its size, the painting looks like it was executed with the rapidity of a sketch.

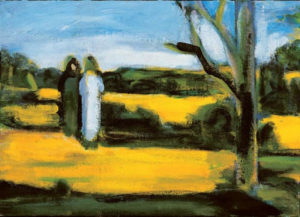

Like Georges and others, Paul Resika studied abstraction with Hans Hofmann in Provincetown. Later, he spent several years in France and Italy, painting landscapes and canal scenes. In the ‘90s, he rented a Thoreau-like cabin in the woods of nearby Oakland where he painted nudes in what looks like a mythical Arcadia. Resika also heard the siren-call of reduction. His paintings of Provincetown harbor, have over the years grown increasingly minimalist . Moon, pier, sailboat and water have been stripped down to their essential geometric forms. Ironically, he has now almost come full circle, back to abstraction.

Peter Heinemann,

Peter Heinemann, who studied with the influential Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, was a longtime teacher at the School of Visual Arts. He has an oval shaped gallery to himself, here, in which the visitor is surrounded by Heinemann’s glaring, blue-eyed self-portraits. These “heads, as he preferred to call them, are painted in an architectonic style, features blocked in with dark lines, and set into Albers-like nested squares of color. They are alternately angry, tragic, grandiose, foolishly romantic, self-critical. In one of the few to include his hands, the artist holds his brush like a wand, fingers at his temple – the artist as magician or swami.

Inspired by the art of Giacometti, Leland Bell enclosed all his figures with black lines in forms almost as simple as cut outs. He animated these schematic characters with high emotion acted out on a domestic stage. In one series a couple’s lovemaking is interrupted by the family cat dropping a bird by the bed. In another, a butterfly in the house causes an uproar. The latter painting is reminiscent of one by Balthus, the French figurative artist who was an inspiration to many of these artists. Coincidentally, that painting, “The Moth,” can be seen in the current Balthus show at the Metropolitan Museum.

Albert Kresch

The other three painters in the show are essentially landscape artists. The best is Albert Kresch, whose small panoramas of hills, fields, water and clouds are reduced to elegant horizontals, bands of dark and light, executed in swift, confident strokes and evoking a twilight poignancy.

Neil Welliver’s bleak canvases of stony fields and log-clogged streams are as anti-romantic as Kresch’s are romantic and are done in a bland paint-by-number style that seems pop-culture ironic. Stan Lewis’s eccentric works are middle- American streetscapes and backyards, painted in drippy oils on paper that is cut up and reassembled. The resulting pictures are as lumpy as real landscapes, while the image that sits on top is as correct as a photograph.

“Mugging of the Muse” by Paul Georges

Painters tend to squirm in bunches. Like the abstract-expressionists who met on Tenth Street, some of these artists gathered for discussions and show-and-tell in a group they called the Alliance of Figurative Artists. Georges captured the ambiance of this bohemian camaraderie in his 1973-74 “Cedar Tavern,” in which prominent members of his milieu huddle closely around a table. Unlike the abstract expressionists, who got famously drunk at the same bar on University Place, these artists are mostly drinking coffee.

That didn’t prevent acrimony. Another Georges painting from the same period, the allegorical “Mugging of the Muse,” portrayed several fellow artists as killers of beauty and resulted in a lawsuit that made national headlines when the plaintiffs were awarded $60,000 in damages. The decision was later overturned.

This show was curated by Bruce Weber, drawing on works owned by the Center for Figurative Painting in Manhattan.