They were the big three of modernist photography, their careers and ideas as intricately bound together as the sound of their names: Stieglitz, Steichen and Strand.

Together, they took a 19th-century medium and brought it up to speed with the artistic revolutions of the early 20th century. In the span of a few decades they had established photography as an art form that could stand on its own two feet, no longer dependent on historic documentation for its relevance and no longer dependent on painterly effects for its aesthetic value.

Their story is told in a compact, artful exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum that is divided into three galleries, one for each artist.

Alfred Stieglitz is the mastermind here, a Hoboken-born whirlwind of creativity and proselytizing who somehow knew all the right things to do in launching an avant-garde movement. He gave his group a radical-sounding name, “Photo-Secession,” that none of the members understood (secession from what?), published them in a sumptuous journal called Camera Work, and exhibited them in a cutting-edge gallery called 291.

Stieglitz’s early photographs of New York City (more can be seen in a show at the Seaport Museum New York) found powerful mood and atmosphere in such gritty scenes as a lone locomotive chugging through yards at Long Island City or the dark watery maw of a ferry terminal.

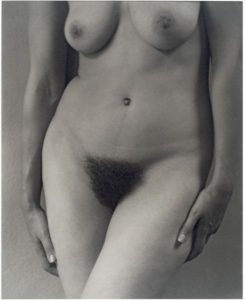

But he is best remembered for his photos of a young painter from Texas, Georgia O’Keeffe, whom he later married and whose fame would eventually eclipse his. Today, the pictures –more than 300 – are a monument to one of the great artist-model relationships. What made them so strikingly modern, however, was the artist’s seeming delight in chopping his model into parts, an act of abstraction akin to modernist painting. The first “portrait” you see here, for example, has no head – only hands and a torso.

Granted, O’Keeffe had beautiful hands, but she had far from beautiful feet, and Stieglitz isolated those as well, just as he did her breasts, her back, her pubis and the taut tendons of her neck. The whole set of pictures is often called a “composite portrait.”

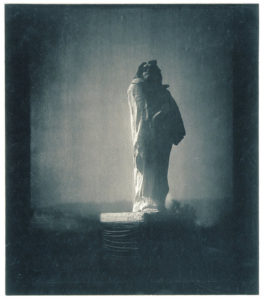

Edward Steichen was trained as a painter and you can see it in his earliest, turn-of-the-century photographs, which are soft-focus, dimly-lit scenes of woodlands and ponds – more like memories of places than real places. Stieglitz paid $5 each for several of them – a vast improvement over the 50 cents Steichen had been getting up to then, and he was soon part of the scene. Steichen spent a lot of time in Paris, where he not only absorbed lessons from painters but sent modernist pictures back to Stieglitz to exhibit at 291.

Steichen’s brooding, poetic “The Flatiron” – shown here in three different prints – was influenced by Whistler’s tonalist “Nocturnes” in the pale, blue-green sky Steichen achieved by adding pigment during the printing process. You can also see the influence of Japanese prints in the way the building’s form is flattened by going off the top of the page, and in the intrusion of the horizontal branch in the foreground.

Stieglitz, Steichen, Strandaise the money to cast it in bronze, had Steichen shoot it outdoors in the moonlight – an ideal setup for the Steichen sensibility.

Paul Strand was a high school student when his teacher, the social documentary photographer Lewis Hine, took his class to Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. He, too, began his career with a pictorialist approach, though his soft-focus scenes were more brightly lit and favored an elevated point of view, often with a small figure, as in in “Winter, Central Park, New York” from 1914, in which a small female figure makes her way across the white landscape.

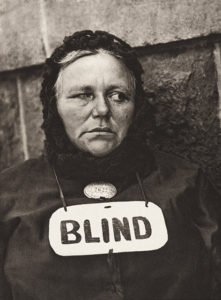

Strand, like Stieglitz, abandoned this dreamy style for a more sharply focused, undoctored photography, that he applied to cubist-inspired still lifes in which tabletops seemingly tip up and bowls in their roundness seem to yearn for geometric purity. In yet another phase, Strand went out into the streets to capture images of ordinary people. In order to get candid expressions, he devised a camera with a fake lens on the front so that he could appear to be photographing someone in front of him, when he was really photographing someone standing to his side.

His famous photo of a beggar blind woman belongs to this humanist phase, though Strand, it would seem, hardly needed the trick camera here to get a candid expression.

Stieglitz, by the way, deserves credit for one more accomplishment. He effectively started the museum’s photography collection by giving it 22 of his own works in 1928. In later decades he gave the museum more than 600 additonal photographs by himself, Steichen, Strand and others. Those gifts made this show possible.