“Do you have secret desires that could be thought of as sinful, immoral, base, or that you personally find squalid, vile, filthy? If so, what do you do? Do you struggle against them, or do you satisfy them in your imagination? Or in real life?”

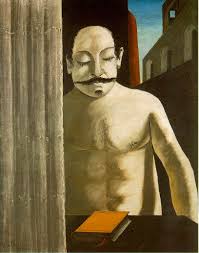

Giorgio de Chirico’s “The Child’s Brain,” was an inspiration for the surrealist movement.

So asks a 1932 survey written and responded to by surrealists and published in one of their own journals. It was typical of the group and reveals the earnestness – bordering on the comical – with which they approached their central preoccupation: desire.

Desire, said surrealism’s founder, poet Andre Breton, was “the sole motivating principle of the world, the only master that humans must recognize.”

“Surrealism: Desire Unbound” at the Metropolitan Museum, a reduced version of an exhibit seen last year at London’s Tate Modern, is a big, yeasty show filled with strange, sometimes outrageous, sometimes disturbing imagery. It’s an unusual undertaking for the usually conservative Met, and an indication of how much things have changed in the museum world. (In fact, with this show, the Irving Penn nudes, and the Costume Institute’s “Extreme Beauty: The Body Transformed,” the Met has, for the moment, become the edgiest museum in town.)

Surrealism was art’s response to Freud’s theories about the unconscious mind. The surrealists peered into this subterranean region of repressed desires, fears, and conflicts and saw a new artistic reality, a “super reality” (surrealite) that would blend the visible and the psychological worlds.

Early surrealism was Alice-in-Wonderlandish, an attempt to insert inexplicable events and objects —fur-lined teacups, floating boulders—into everyday life. But by the late Twenties and early Thirties, artists and poets were focusing more and more on erotic themes, with desire — enfolding both love and sex — as the true voice of the inner self.

Max Ernst’s “Robing of the Bride.”

Surrealism had its hard core – poets Breton and Paul Eluard, artists Salvador Dali, Man Ray, Max Ernst, Hans Bellmer, and Andre Masson – but the exhibit also devotes space to the non-card-carrying types and fellow travelers such as Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Joseph Cornell, Joan Miro, and Jean Arp.

The hard-core had a dark side—they revered the Marquis de Sade, and their work sometimes crossed over into pornography —but they also had an endearing bohemian spirit. They were given to attention-getting stunts, sexual scandals, and fervid half-religious crises. At times, they functioned like a political party, preaching social revolution and publishing manifestos in their own magazines and journals.

The movement had its roots in a revelatory moment when Breton, passing a gallery in a bus, saw a painting in the window and jumped off to have a look. The year was 1916, and the painting was Giorgio de Chirico’s “The Child’s Brain,” an enigmatic evocation of the artist’s father, a bare-chested, mustachioed man whose eyes are closed meditatively and who, in true Oedipal fashion, looks both menacing and seductive. Breton later bought the painting, which hung over his bed for most of his life. De Chirico proved a further inspiration with his dream-like paintings of starkly sunlit plazas with their phallic smokestacks and brooding, dark archways. Later, when his work took a different turn, he lost the surrealist seal of approval.

That was how it was with them. The surrealists were forever passing judgment and drumming people out of the group. Giacometti, for example, created some of the most powerful sculptures in the surrealist genre, such as his violently erotic “Woman With Her Throat Cut.” But, when his style veered toward straight observation, he was branded a traitor to the cause.

Salvador Dali presented an opposite problem. He embraced the surrealist program so enthusiastically and indulged his own neurotic sexual hangups so vividly that he made even this broad-minded group uncomfortable. In Dali, you also see surrealism’s weakness for practical jokes: “Venus With Drawers,” the exhibit’s introductory piece, is a copy of a famous Greek statue fitted out with dresser drawers.

Restraint was not a strong point with the surrealists. Painters like Max Ernst and Andre Masson were so intent on getting their unconscious minds onto canvas that they sometimes lost sight of just how garish and over the top these pictures became. Ernst’s “Robing of the Bride” is as bizarre as anything by Hieronymous Bosch, with its owl-headed bride, attended by several monstrosities, including a green, four-breasted, web-footed hermaphrodite who looks to be in her third trimester of pregnancy.

“Birthday,” by Dorothea Tanning.

Ernst, by the way, also had a singular talent for entanglements with young women who were either gifted, rich, or both. At 45, the charismatic artist divorced his first wife and ran off with Leonora Carrington, daughter of a wealthy industrialist and an artist who was even more Boschian than he was. Later he married heiress and art patron Peggy Guggenheim, but left her for Dorothea Tanning, a 30-year-old New York artist whose beauty, chess-playing abilities, and surrealist style made her an Ernstian dream come true. The exhibit has the painting that was on the easel when Ernst first visited her apartment: an arresting self-portrait that shows Tanning bare-breasted in fairy tale garb, standing in a labyrinthine space with a winged lemur at her feet.

Gender bending was another surrealist game. Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp both posed for the camera in drag, Duchamp in the guise of his alter ego, Rrose Selavy (Eros, c’est la vie, or Eros, that’s life), who, despite her name, looked rather dowdy. Ray also played another game, crafting images that combined maleness and femaleness: a photo of a woman with her head tilted back, so that neck and thrust-up chin present a distinctly phallic form. Ernst’s emblematic “Men Shall Know Nothing of This” was inspired by the memoir of a paranoid schizophrenic who imagined himself as both man and woman having intercourse with himself.

One of Hans Bellmer’s dolls.

Kink reached its apex in the work of Hans Bellmer, an artist with a peculiar gift for drawing that elevated even pornographic subjects to the level of art. His fetishistic masterpiece was a life-size doll, a child-woman made with a movable ball-joint design that allowed him to create provocative poses, which he then photographed. Sometimes Bellmer played Dr. Frankenstein, mixing up the body parts. In one, he replaced the upper torso with a second set of legs. Breton and Eluard praised the doll’s “universal, provocative power.”

No surrealist show would be complete without Rene Magritte, the only truly popular surrealist. The Belgian was mild for this company. He was the master of the double-take, jolting viewers with neatly painted snapshots of the impossible – the apple that fills a room, the nighttime street with the bright blue sky above. Even when the subject was sexual – the famous image of the pubic face, or “The Lovers,” two anonymous heads kissing through gray hoods, he was more a puzzlemaker than an erotic artist.

The exhibit ends on something of a down note, with many of the surrealists leaving France for the United States during World War II. New York became the ostensible center of surrealism, but it never really flourished here. Breton was unhappy in New York and refused to learn English. Surrealism was absorbed into what became abstract expressionism, especially in the works of Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock, whose works are among the last we see.

More than any individual work, it is the surrealist spirit that shines through in this exhibit. They were often over the top – as with the Canadian surrealist whose tribute to the Marquis de Sade included a dance with a strapped-on phallus and culminated with a self-branding with a hot iron—but they were sincere in the reinterpretation of human nature and their attempts to live on the edge. The free-love atmosphere was not all fun and games. You can see the emotional cost in a convoluted letter from Man Ray to his lover, Lee Miller, in which the photographer struggles to be lighthearted and liberated about her affairs, but fails miserably.

Surrealist art can be like listening to another person’s dream—the weirdness is often more fascinating to the teller than the listener, and “Surrealism: Desire Unbound,” is an uneven show—but it’s hard to imagine a surrealist show that wouldn’t be.

Surrealism was like a labyrinthine castle, a mixture of Gothic spookiness and fairy tale fancy, complete with dizzying towers and dank dungeons in which the strangeness, the oddity of each room was what counted, not the elegance or unity of the layout.

Metropolitan Museum

2002