An art exhibit devoted to Victorian nudes might raise low expectations. Here, it seems to say, are the erotic yearnings from a period whose most salient characteristic was its prudery.

An art exhibit devoted to Victorian nudes might raise low expectations. Here, it seems to say, are the erotic yearnings from a period whose most salient characteristic was its prudery.

But repression can do wonders for fantasy life. Art is about sublimation. That’s what makes this show at the Brooklyn Museum so much fun, where similarly inclined shows of contemporary art, such as “Sensation,” have been anything but. When postmodern artists try to arouse, they tend to get overly clinical, or ironic, or cynical. But the premodern Victorians played it straight. Once you adjust to the level of kitsch, and begin to see this stuff with Victorian eyes, a hothouse of imagination opens up.

Organized by Tate Britain, the show has about 150 works, from paintings of mermaids and fairies to sculptures of naked slaves, to hilarious pornography by Aubrey Beardsley to borderline kiddie porn by Lewis Carroll to naughty “What-the-Butler-Saw” films that were shown in turn of-the-century penny arcades.

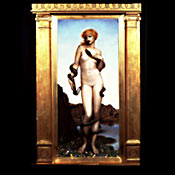

Queen Victoria’s reign lasted 64 years, from 1837 to 1901, and the show is organized somewhat chronologically, with works grouped by themes such as “The Classical Nude” and “The Artist’s Studio.” A more daring organization might have grouped works by the nature of the fantasy. The Victorians were very adept at using mythology and symbolism to venture into otherwise forbidden areas.

Voyeurism, for example, found expression in the women-surprised-bathing motif. As popularized by artists such as William Etty and William Mulready, they show virginal maidens being spied upon while skinny dipping. Some blush modestly, while others seem either curiously unaware or disinclined to cover up.

Female exhibitionism? What better tale than that of Lady Godiva, the 11th century noblewoman who rode naked through the streets of Coventry for the cause of tax relief? The town folk were ordered not to look, however, and in Edwin Landseer’s painting a matron keeps her eyes clamped shut, while doves seem to avert their eyes.

In polite Victorian society, women didn’t have sexual urges. So, when artists wished to depict an aggressively lustful woman, they turned to sirens or mermaids. In a painting by Frederic Leighton, a sleepy young fisherman gets more than he bargained for when a lithe mermaid springs up from the sea and embraces him.

Bondage was another popular motif with the Victorians. There are no shortage of paintings of women tied up, from Andromeda, the princess chained to a rock as a sacrifice to a sea monster, to the damsel in distress – John Everett Millais’ painting of the woman rescued by the knight (there’s a little additional kink here in the contrast between the fully armored man and the completely nude woman).

Bondage was another popular motif with the Victorians. There are no shortage of paintings of women tied up, from Andromeda, the princess chained to a rock as a sacrifice to a sea monster, to the damsel in distress – John Everett Millais’ painting of the woman rescued by the knight (there’s a little additional kink here in the contrast between the fully armored man and the completely nude woman).

Things get a little out of hand in Herbert Schmalz’s scene of Christian martyrdom in which seven nude women, bound to posts, await the onslaught of the lions in the Roman Coliseum.

Whatever their different sexual turn-ons, Victorian artists did seem to agree on the ideal feminine body. In contrast to the popular hourglass look imparted by corsets, the artists favored a more classical figure: a delicate torso (the buxom figure is nowhere to be found here) with a roundness and fullness to the waist, hips, and thighs, emphasizing women’s natural reproductive role.

Naturalness didn’t extend to body hair, however. The great Victorian art critic John Ruskin, whose concept of the female body was apparently formed by Greek and Roman statuary, was reportedly horrified on his wedding night to discover that his wife, Effie Gray, had pubic hair. The spurned Effie eventually left him for Millais, but, almost without exception, artists persisted in painting women with mannequin-like pudendas.

What they couldn’t paint outright, however, the Victorian artists found symbolic substitutes for. Lawrence Alma Tadema’s reclining nude shields herself with a strategically placed ostrich feather fan, but the animal fur that spills out from beneath her more than gets the idea across. Phallic symbols abound, as do various dark openings in the form of shells or baskets. Some of the artists indulge in the kinds of visual games more typical of an Austin Powers movie, as when a turned-out thumb emerges from clasped hands just where the penis would be.

What they couldn’t paint outright, however, the Victorian artists found symbolic substitutes for. Lawrence Alma Tadema’s reclining nude shields herself with a strategically placed ostrich feather fan, but the animal fur that spills out from beneath her more than gets the idea across. Phallic symbols abound, as do various dark openings in the form of shells or baskets. Some of the artists indulge in the kinds of visual games more typical of an Austin Powers movie, as when a turned-out thumb emerges from clasped hands just where the penis would be.

Among the artists who wren’t anatomically shy was Aubrey Beardsley. In his humorous, pornographic ink drawings, men have cartoonishly large phalluses. Many of his works were made under commission by a publisher named Leonard Smithers, whom Oscar Wilde once called “the most learned eroto-maniac in Europe.”

The blanket notion of prudishness is a bit hard to maintain in view of the Victorian tolerance for child prostitution, and where milder forms of pedophilia were indulged with photographs of nude prepubescent boys and girls. Among the practitioners of this genre was Charles Dodgson, who wrote the “Alice in Wonderland” books under the pen name of Lewis Carroll. He maintained that there was nothing indecent or inappropriate about this, as long as there was consent and parental supervision, even when he posed a little girl name Evelyn Hatch in the seductive reclining pose of Titian’s “Venus.”

In the last section, the “Modern Nude,” artists finally abandon the mythical pretexts. No more distressed damsels, Nubian slaves, or winged fairies. Just nude women, sitting on a bed, reading a magazine, or staring straight back at you. The honesty is refreshing, as is the looser, painting style, but reality can seem harsh, as well. That’s especially true in the case of expressionist artist Walter Sickert. The exhibit never mentions it, but a strong case has been made that Sickert was the real-life Jack the Ripper. You don’t have to be sold on his guilt to see something disturbing in his paintings of women with their heads abruptly cropped out, or their faces rendered with rough, disfiguring strokes.

Kitsch or no kitsch, it makes you nostalgic for the world that came before.

Brooklyn Museum

September, 2002