Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, a 19th century French homeopathic physician and dabbler in art, would be totally unknown to us had he not been a neighbor of the impressionist painter Camille Pissarro. Gachet traded medical services for paintings and, through Pissarro, met other impressionists, whose work he admired and collected.

Then, in 1890, Pissarro brought together Gachet and a mentally imbalanced Dutch painter who longed to leave his asylum but needed looking after. So it happened that Vincent van Gogh became the patient of the eccentric Gachet, who supported the artist’s creative efforts but could do little to prevent another psychotic episode.

Then, in 1890, Pissarro brought together Gachet and a mentally imbalanced Dutch painter who longed to leave his asylum but needed looking after. So it happened that Vincent van Gogh became the patient of the eccentric Gachet, who supported the artist’s creative efforts but could do little to prevent another psychotic episode.

Indeed, Van Gogh seemed to see the hopelessness of his situation when he wrote to his brother Theo: “I think we must not count on Dr. Gachet at all. First of all, he is sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much, so that’s that. Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don’t they both fall into the ditch?”

Seventy days after his arrival in Auvers, Van Gogh shot himself and died two days later, Gachet at his side.

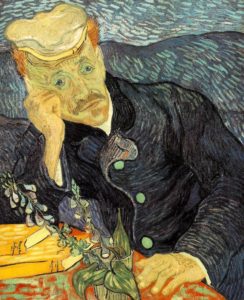

Gachet wound up with 26 Van Goghs, and he and his equally eccentric son, Paul, became keepers of the Van Gogh flame for the next half-century. Artist and physician became forever linked in the public imagination in 1990 when a portrait of Dr. Gachet (which Van Gogh described as having “the heartbroken expression of our time”) sold at auction for a record $82.5 million.

In the worshipful attitude that now surrounds Van Gogh, the strange Gachets have come under close scrutiny, some of it negative. Gachet has been called negligent both as psychiatrist and physician (as the artist lay dying, he made a famous sketch of his face), and greedy (for the supposed haste with which he and his son gathered up the paintings left in Van Gogh’s room). The reclusive son, who kept scholars away from the collection for decades even as he and his sister lived exclusively off the sale of selected pictures, has been accused of forging Van Goghs.

Now, in an exhibit originating in Paris and currently at the Metropolitan Museum, the Gachets are shown warts and all, but in a more sympathetic light. The emphasis is on Gachet the collector and on the paintings, not only by Van Gogh, but by Pissarro, Cezanne, Monet, Renoir, and others attracted to the scene.

There are only a handful of really great paintings in this show – an intense, almost mystical self-portrait by Van Gogh in which the torso and head are set off against a swirling, blue-green background; the ominous “Church at Auvers,” in which the gray, clumsy structure is set against a deep, deep blue sky refected in the Gothic windows, giving the church a sense of having nothing inside; a second, darker version of “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” that was once branded a forgery but, if so, by a forger with a brilliant command of Van Gogh’s forceful brushstrokes; a moody, cloudy-day view of Dr. Gachet’s house by Cezanne during his Pissarro apprenticeship; and Pissarro’s mysterious and poetic winter scene, “Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes,” in which a snow-covered red house is set back behind gnarled trees, and a mother and child, all bundled up, stand stiffly in the snow.

There are a few clunkers in the show – a painter could hardly be expected to give one of his best paintings in exchange for the treatment of some minor ailment. The show also has impressionist copies by Gachet, who painted under the pseudonym of Paul van Ryssel. The younger Gachet also painted, often in the style of one of the painters he admired, as in the case of his portrait of Vincent van Gogh’s mother (and which is competent enough to have fueled the speculation about forgeries).

Gachet was an ever-willing sitter for portraits. His eccentricity sometimes comes through, not least of all in a portrait by his own son, who depicted him as a scholar and man of science, dressed in physician’s attire with his hand on a skull. But the costume and the attempt at a noble expression make him look ludicrous and clown-like.

Whatever strange personality traits he had, and whatever his failings as a psychiatrist or physician, Gachet turned out to be an unusually astute collector of art, all the more so because he was by no means wealthy. At a time when no one wanted to buy Van Gogh’s work, Gachet recognized his genius, writing to Theo after his death that he thought of Van Gogh as “a Colossus” and a painter of religious intensity. Cezanne was still struggling to find himself when Gachet met him, but the doctor saw enough of Cezanne’s greatness to rescue unfinished and unsuccessful paintings, some on cardboard, that would otherwise have been lost.

Van Gogh said of Gachet that “he loves art for art’s sake,” and this comes across in his earnest copying of the works he admired and his attempts, as an amateur, to make his own art. These efforts, and his genuine enjoyment of artists’ company, gave his appreciation of art a depth that few collectors achieve.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1999