In the 1956 movie “Lust for Life,” there is a scene in which Vincent Van Gogh (played by Kirk Douglas) has figured out a way to paint outdoors at night: he puts candles around the brim of his straw hat.

The story is apocryphal. But the image always stuck in my mind, not just because it made Van Gogh look like such a nutcase, but because it captures both the truth and the myth about the man. Yes, he had a passion for painting outdoors, yes, he loved nighttime scenes, and yes, he suffered from manic episodes that interfered with his work. But no, he wasn’t a kook with candles on his hat or a visionary who saw hallucinatory swirls in the heavenly dome.

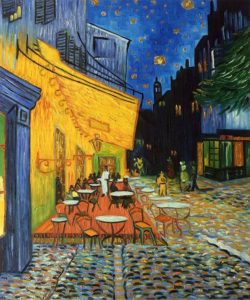

“Cafe Terrace at Night.”

“Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night,” which opens today at the Museum of Modern Art, shines intelligence and insight on a previously unexhibited theme in the work of a much-exhibited artist. MoMA is a natural to do this, since it owns Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night,” the most famous nocturnal scene in Western art.

This is a small show — only 23 paintings and ten works on paper – and even some of these seem tangential to the topic (like the one of Gauguin’s chair with a candle on the seat). You could probably tell this show’s story with as few as ten oils.

That’s because Van Gogh himself does a lot of the curatorial heavy lifting. His letters – eloquent, powerfully descriptive and often illustrated with sketches — are the narrative spine. Like a good short story, the exhibit devolves around a problem: how to paint nighttime scenes with a new impressionist palette and plein air technique.

“Starry Night Over the Rhone.”

Most exhibits treat the somber-toned paintings of Van Gogh’s Dutch period as an almost irrelevant prelude to the impressionist-inspired breakthrough of 1885 to 1890. But this one’s theme cinches together the two halves of his ten-year career. Paintings of romantic twilight landscapes, cottages with glowing windows, and especially the Rembrandtesque dimly-lit interior of “The Potato Eaters” feel of a piece with the nighttime works that followed.

The Arles painting linked to the candles-on-the-hat scene in “Lust for Life” was “Starry Night over the Rhone” of 1888. It has two sources of light: stars (including the Big Dipper) – and wavy reflections of gas lamps across the river’s width. Nearby gas lamps provided Van Gogh with the light he needed to paint in the dark.

Stars had made a cameo appearance in a painting he did earlier that same month, “Cafe Terrace at Night.” Although it’s not in the show, there’s a sketch and a letter describing it to his sister: “It amuses me enormously to paint the night right on the spot. Normally, one draws and paints the painting during the daytime after the sketch. But I like to paint the thing immediately.” He acknowledges that in darkness he may confuse blue for a green, or “blue lilac for a pink lilac, since it is hard to distinguish the quality of the tone,” but finds this preferable to “the poor pale whitish light” of studio-painted night scenes.

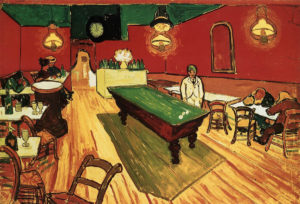

“The Night Cafe.”

At the other end of the poetic spectrum is “The Night Café,” in which, he confided to his brother, Theo, he wanted to paint “the café as a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad or commit a crime.”

In a red-wall, green-ceiling room men sleep in chairs beneath the glare of yellow gas lamps. At center stage, a local “hooligan” stands at a pool table, beneath which an ominous shadow advances.

In MoMA’s “The Starry Night” (1889) imagination played as big a part as observation. Perhaps because it was painted in the asylum at Saint-Remy, some have suggested that the swirls and halos were what Van Gogh’s feverish brain actually registered. But the letters and close study of the painting have shown how carefully and thoughtfully Van Gogh the artist modulated these effects.

Which is not to say the painting wasn’t borne of deep feeling. This comes across in a letter that predated the painting: “I have a terrible need of– dare I say — religion…then I go outside at night and paint the stars.”